What's discussed in this post

Introduction

You just finished your draft. Congratulations!

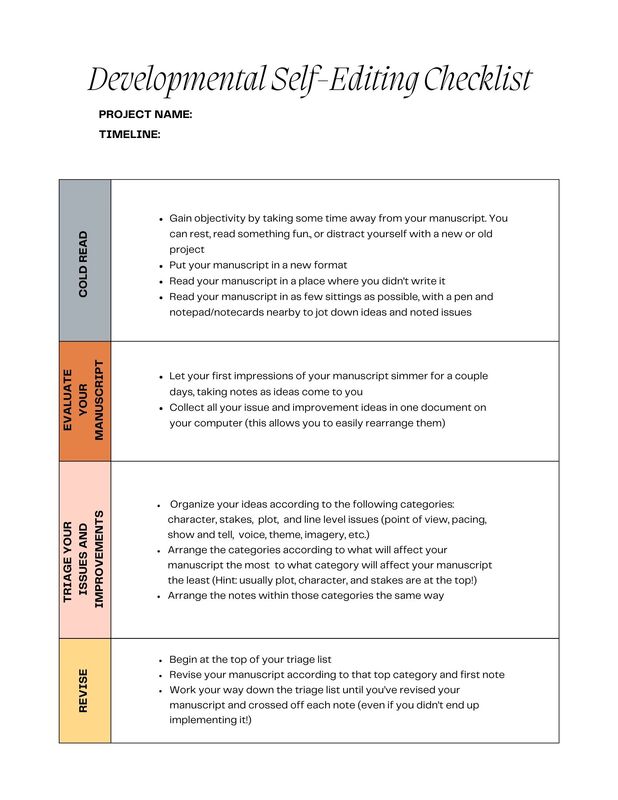

… Now what? Even for the experienced author, revising a short story or novel can be a daunting task because the advice out there is often this broad or vague. Authors need specific and actionable advice so they feel confident in approaching a revision. That’s where the developmental edit comes in. A developmental edit is an evaluation of a manuscript's bigger picture (or macro) elements, which includes character, stakes, and plot. It may also address some micro edits such as pacing, structure, showing and telling, point of view, and tension. The point is to get the bones of the story in proper shape. While hiring a professional to perform a developmental edit or editorial critique is always a good option, every author should attempt to do it themselves first. Learning to evaluate your own manuscript will not only help you hone your craft, but it will save you money. The structure of a developmental self-edit

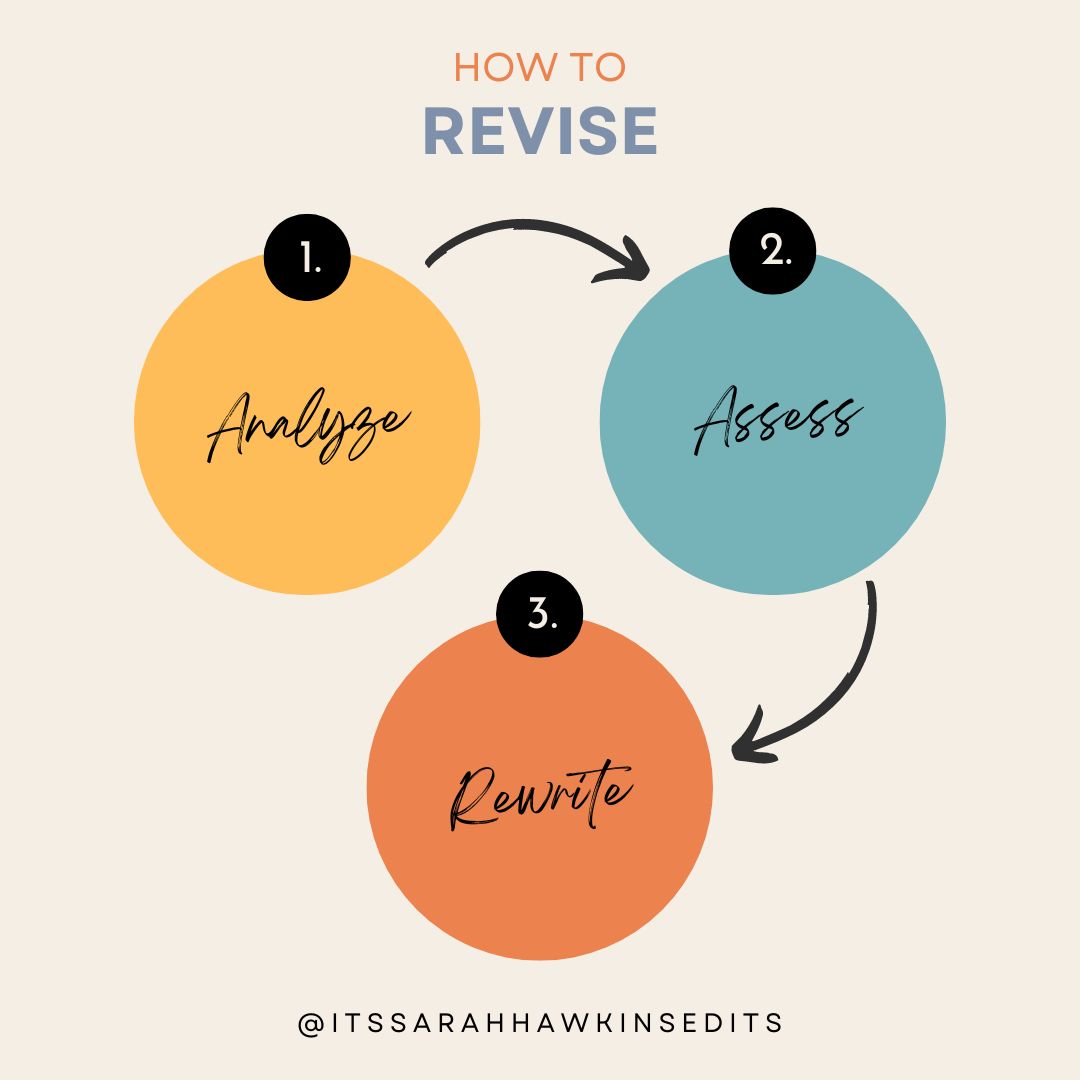

So, what is the structure of a developmental self-edit? Here’s the basic outline:

This post goes into how to perform a cold read. By the end, my hope is that you can approach this first step of revising your manuscript with confidence and clarity. What is a cold read and how do you do one?

For a developmental editor, the cold read is the first read-through of the manuscript. Reading through the manuscript prior to digging into a developmental edit allows an editor to get an overall feel of the manuscript’s character, plot, stakes, and themes; the author’s style; and the obvious issues to address. Typically, no actual editing is performed on this first read, but the editor will have a checklist or notepad nearby to jot down notes or ideas.

A cold read is more easily done by a developmental editor because the manuscript isn’t precious to them. They go into the read with the needed objectivity. As the author, you don’t have that advantage. So, the first step of performing a cold read is to gain objectivity, and the second step is the read-through. Step 1: Gain objectivity

What you and your manuscript really need is objectivity. Here are three ways to help you get it:

1. Take time and distance away from your manuscript

Established authors, editors, agents, and book coaches all emphasize the importance of stepping away from your manuscript, giving it (and you) time to rest. I’ve seen many suggest letting the manuscript rest for at least six (6) weeks. This is often easier said than done. Sometimes, we are too excited to put our manuscript aside for long, and other times, we are on deadline, whether self-imposed or not. However, Tiffany Yates Martin says even a few days away from the manuscript can be effective—if you distract yourself. Here are some distraction methods:

General Revision – Intuitive Editing by Tiffany Yates Martin. I cannot recommend this book enough. It’s the first book on revision with clear, practical, and actionable advice. It makes my neurodivergent brain happy.

Show vs. Tell – I haven’t seen a better book on showing and telling than Understanding Show, Don’t Tell (And Really Getting It): Learn how to find—and fix—told prose in your writing by Janice Hardy. Like Intuitive Editing (which has a chapter on this!), Hardy’s book gives actionable advice with great examples. Both books have the format of “how to find it and how to fix it,” which I find extremely helpful!

Short stories have the added benefit of helping you hone your craft while you create something for your newsletter. Pick up Brevity: A Flash Fiction Handbook by David Galef to learn about the different formats of flash fiction and how to revise it.

Tip: Explore a new genre through a short story. It will distract you even further from the book you just finished.

2. Read the manuscript in a different place than you wrote it

As Yates Martin says, “The brain is a creature of habit.” So, if you try to read your manuscript in the same place as you wrote the draft, your brain will go back into writing mode. You want it in reader mode!

3. Read the manuscript in a new format

This is an essential part of the editing process, I believe. Putting your manuscript in a new format—whether it's a printout, a paperback ordered off of Lulu, on your e-reader, or even with just a different font—tricks your brain into thinking it's not yours and therefore allows you to enjoy it as a reader would.

Step 2: Read your manuscript

Next, you’ll want to read your manuscript in as few sittings as possible. Make sure you have a notepad, notecards, etc. nearby to jot down issues you notice or improvement ideas. DO NOT mark up the manuscript itself (which is why putting it on an ebook reader is such a brilliant idea). If you begin marking up the manuscript, your brain will flip into writer and revision mode, and we’re only focusing on identifying issues and improvements right now.

Also, don't forget to write down good things about your manuscript! What did you enjoy? What is working? Highlight your favorite lines! You'll be happy to have a reminder of what is good about your manuscript as you dig into the revisions. Once you're done with your cold read, it's time to let your first impressions simmer. Our unconscious discovers wonderful ideas when we let it. Leave your manuscript for a couple of days, let your unconscious do its magic, and never be without the means to take notes! To sum it up

Every author should learn how to perform a developmental self-edit because it will not only help them hone their craft but also save them money. A cold read is the first step of a developmental self-edit, and to perform an effective cold read, you need to obtain objectivity. Take time away from your manuscript if you can, and if not, read your manuscript in a new format and a new place than you wrote it. Read your manuscript in as few sittings as possible, and then let your unconscious work its magic before you start on the next step: Evaluating your manuscript.

0 Comments

What's discussed in this post

What is cohesion and why is it important?

When reader expectation is not met, the narrative may read awkwardly, causing the reader’s concentration to break briefly or the reader to backtrack to glean meaning out of what they just read. This disrupts the reader’s immersion and gives them the opportunity to put down your book! No one wants that. This guide explains how to meet reader expectation at the paragraph level with the known-new contract, so you can revise your writing for cohesion with confidence. What is the known-new contract and how does it apply to paragraphs?As explained in my post, “How to meet reader expectation at the sentence level,” the known-new contract is how the reader learns new information: by connecting it to what they already know. If you struggle with meeting the known-new contract, your sentences may provide only new information consecutively, creating a choppy, disconnected flow. At the paragraph level, the known-new contract begins with the opening sentence. Reader expectation is set in that first sentence because it tells the reader what is coming. Essentially, the first sentence of every paragraph acts as a topic sentence, and the sentences that follow act like subtopics or supporting details.

The 3 paragraph patternsThere are 3 paragraph patterns that every writer should be aware of:

The repeated topic paragraph patternAs inferred in the name of the pattern, the repeated topic paragraph pattern takes full advantage of repetition as a cohesive tool. The topic presented in the first sentence becomes the known information for the full paragraph, and this known information regularly remains in the subject position, although the phrasing of the subject may change to synonyms, related words, or pronouns to create variety. This paragraph pattern works for:

Examples

Here, LaCour introduces the topic of “a speech” that the narrator has prepared, and then uses the repeated pronoun “It” to refer back to the topic, the speech, while adding supporting detail to create depth to the speech without us having to hear it all. The pronoun “it” doesn’t have any other meaning until the direct speech quote. Not only is it a prime example of the repeated topic paragraph pattern, but it’s also a great example of balancing showing and telling with description. (If you want to study description, I highly recommend Everything Leads to You!)

Like LaCour, Barrow uses a repeated pronoun and its antecedent to move the reader through this paragraph. Unlike the LaCour example, the topic of this paragraph—Hannah’s relationship to smoking—is not stated outright, but it is no less clear through her lighting the cigarette and the act of smoking instantly soothing her. Barrow then uses not only a repeated pronoun and its antecedent (Hannah, she, her) but also related words (cigarette, click-hiss-exhale, the thing, a big smoker, something, that, the smoking, it, a way not to drink). The known-new paragraph patternThe known-new pattern allows the topic of the sentence to progressively change throughout the paragraph by using the new information in one sentence as the known information in the next. So, the information in the predicate becomes the subject of the next sentence, and each sentence after the topic sentence acts either as a subtopic of the first sentence, or a supporting detail of the sentence directly before it. This type of paragraph pattern works for:

Examples Here, Hahn uses the known-new contract to introduce a new character to this scene. The predicate of the first sentence, even as my phone buzzes with a text, sets up the introduction and leaves the reader asking Who? The question is answered immediately as the subject of the next sentence: Micah. We then find out what Micah’s doing, what his motivations are, and why. This is a short paragraph of 2 sentences and therefore highlights cohesion at the sentence level as well as paragraph level. Barrow uses the known-new contract to introduce multiple characters to the narrator’s life: he sees the band, and we find out who is in the band. The information paragraph patternIn the information pattern, each sentence after the first sentence is a supporting detail of the topic. The supporting details act as subtopics, and they are all known information because they are in the same domain as the topic sentence. They are information that a reader expects as relevant. This works for:

Examples See? I told you that you should read Everything Leads to You if you want to study description! LaCour uses the information pattern here to describe a character’s house. Each subject in the independent clauses that follow I pull up in front of her house is a subtopic: the shutters in the front windows, junk mail, a few small pots. Even though it’s all new information, it’s what the reader would expect to learn about a house, and therefore it acts as known information to them.

Here, Hahn uses the information pattern for an introspective paragraph. The topic is the narrator wondering if he’s ruined her for anyone else and how effed up that is (Hahn uses a fragment here for dramatic effect, but the first two sentences are one idea). Each subject of the subsequent sentences act as subtopics staying in the domain of her explaining why that thought is effed up. Quick tips

Further study

What's discussed in this post

What is cohesion and why is it important?

When reader expectation is not met, the narrative may read awkwardly, causing the reader’s concentration to break briefly or the reader to backtrack to glean meaning out of what they just read. This disrupts the reader’s immersion and gives them the opportunity to put down your book! This guide explains how to meet reader expectation at the sentence level with the known-new contract, repetition, and parallelism, so you can revise your sentences for cohesion with confidence. The known-new contractOut of the 3 techniques used to create cohesion, the known-new contract is the most important because it’s how the reader learns new information: by connecting it to what they already know. If you struggle with meeting the known-new contract, your sentences may provide new information consecutively, creating a choppy, disconnected flow. To understand this concept, we need to go over how sentences present information:

Starting with a simpler concept of what the reader already knows de-emphasizes it and allows the reader to focus and understand the new information. The new information should be presented in the predicate, where the natural emphasis is, because it allows the reader to retain more complex information and carry it onto the next sentence.

This sentence couplet comes in the scene right after the protagonist, Icelyn’s pet mini-dragon (Ember) had gone missing, sending Icelyn into a depressed panic. Since the reader would already have that in the foreground of their mind, Clemens begins the sentence with Ember finding her way home yesterday and ends with how Icelyn feels today about it, was such a relief it made today feel brighter, which is new information to the reader. In this case, the known-new contract also has a cause-effect structure. Clemens uses cause-effect to connect the first sentence to the second. The effect of Icelyn Humming a winter tune isn’t new information because it is caused by and exemplifies Icelyn’s relief making the day feel brighter, and those emotions are pulled through and motivate Icelyn’s actions in the rest of the sentence. RepetitionThis may seem like a promotion for redundancy, but there’s a major difference between redundancy created through repetition and repetition as lexical cohesion. When repetition is used as a cohesive tool, it acts as a link between sentences. It’s the known in the known-new contract, allowing the reader to focus on the new information, the purpose of the sentence. Repetition only becomes redundant when it has no purpose. Additionally, as stated above, lexical cohesion isn’t only the repetition of words and phrases; it includes the use of synonyms and related words, such as pronouns. Using pronouns is one of the easiest ways to create lexical cohesion because the subject or direct object of one sentence can be the subject of the next, yet they still add variety. Here’s an example of lexical cohesion using pronouns from my work-in-progress, Girls to the Front: We set down the desk in the main room, and I greet Nana. She sits in her usual house dress on the living room couch, watching Murder, She Wrote reruns. The direct object of the sentence I greet Nana sets the reader’s expectation to see Nana in the next sentence. Since Nana is in the foreground of the reader’s consciousness, the use of the pronoun she links two sentences together naturally, and the reader’s expectations are met. A more advanced way to create lexical cohesion is to use a scheme of repetition. A scheme is a structure used to convey meaning. Schemes of repetition include isocolon, anaphora, alliteration, assonance, epistrophe, epanalepsis, anadiplosis, antimetabole, and polyptoton. (I’m going to talk about these in a future post. Stay tuned!) ParallelismParallelism becomes a cohesive device when it’s used to connect sentences and paragraphs by creating an echo structure across them. When you echo a structure from one sentence to another (or one paragraph to another), you remind the reader what should be in the foreground of their mind. This adds intensity and drama. Here’s an example from Girls to the Front: Over the last few years, the church transformed the old school gym into an all-in-one kids entertainment center, with a set of trampolines, a video game setup, and an enclosed, padded play area (for the littlest kids) on the left; and an obstacle course made of ropes, beams, and climbing structures on the right. Here, I use parallel structures to concisely describe a setting. A set of trampolines, a video game setup, and an enclosed, padded area (for the littlest kids) and an obstacle course made of ropes, beams, and climbing structures both consist of three parallel noun phrases. The parallel prepositional phrases on the left and on the right connect the two descriptions to create one image. Finally, parallelism can also be used in the scheme antithesis, which is a comparison of contrasting ideas. An example of parallelism used in antithesis is Neil Armstrong’s famous “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Quick tipsHere are some quick tips based on what we’ve learned in this post:

Further studyStyle and Statement by Edward P.J. Corbett and Robert J. Connors

Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects by Martha Kolln and Loretta Gray Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace by Joseph M. Williams and Joseph Bizup What's discussed in this postIntroduction Basic functions Basic function 1: to introduce a series or list Basic function 2: to separate numeric terms Basic function 3: to separate a title and subtitle Basic function 4: to introduce a quotation, or to separate a formal greeting from the message Stylistic Functions Stylistic Function 1: to create an informal tone Stylistic Function 2: to illustrate or add emphasis Stylistic Function 2: to add sizzle Other editorial considerations Colons and capitalization Colons and other punctuation Further study IntroductionIt is my personal opinion that colons are the most underrated punctuation mark. Many authors avoid using it, probably because of how it was introduced in grade-school English class: with limited functionality and formal tone, so it seems incompatible with fiction writing, which generally has an informal tone. But the colon can be used effectively in fiction writing to create an informal tone and drama. This guide is meant to help you understand the colon’s basic and stylistic functions, as well as the editorial considerations regarding the colon, such as capitalizing, typeface, and other punctuation, so that you can use it with confidence as part of your writing stylekit. Basic functionsHere is an overview of the basic functions of the punctuation, the colon. Basic function 1: to introduce a series or listA colon (:) is used to introduce a series or list. The introductory clause before a colon must be an independent clause (complete sentence) and can include phrases such as “the following,” and “as follows.” The list or series the colon introduces can consist of words, phrases, and clauses (even independent ones). Basic function 2: to separate numeric termsA colon is used to separate the following numeric terms:

Basic function 3: to separate a title and subtitleIn running text and other citations, a colon is used between the main title of a book and its subtitle (The Best Punctation Book, Period: A Comprehensive Guide for Every Writer, Editor, Student, Businessperson). Basic function 4: to introduce a quotation, or to separate a formal greeting from the messageA colon is commonly used to introduce quotations following a complete sentence, especially if the quotation is a block quotation. A colon can also be used after a formal greeting within an email, letter, or other missive (Dear Mr. Darcy:). Stylistic functionsColons can also be used stylistically to create an informal tone and add drama. Use these stylistic functions sparingly in your fiction writing: if they are used too often, they will lose their effect! Stylistic function 1: to create an informal toneSome of the colon’s basic functions can be used to create an informal tone in the following ways:

Stylistic function 2: to illustrate or add emphasisA colon (:) can be used between two independent clauses in the same way a semicolon (;) is. In fact, sometimes they are interchangeable, but it’s important to note that while a semicolon represents the coordinating conjunction “and,” the colon represents the subordinating conjunction of “because.” Therefore, the clause that follows the colon should answer, amplify, or illustrate what precedes the colon. Stylistic Function 3: to add sizzleTo understand this stylistic function of the colon, we must first go over the type of pause the colon creates and what punctuation signal the colon represents when it’s used between two clauses. The easiest way to do this is to compare it to the semicolon (;). Like the semicolon, the colon creates a pause that’s somewhere between the quick breath of a comma and the full stop of an ending punctuation mark (period, question mark, and exclamation point). But a colon represents a different type of signal than a semicolon. While a semicolon represents the flashing red signal of “and,” a colon represents a flashing yellow signal of “proceed.” In other words, the colon prepares the reader’s mind for something that is coming. It creates anticipation, expectation, and excitement. It creates sizzle. This function is most commonly used when a colon connects two independent clauses. But it also allows you to use the colon to add drama while introducing a dependent clause. Just make sure the dependent clause elaborates on the statement in the introductory clause! Other editorial considerationsThis section offers a brief overview of the editorial considerations you must be aware of when you incorporate colons into your writing. Colons and capitalizationWhether or not to capitalize what comes after a colon is based on syntax:

Colons and other punctuationThe colon can be used in conjunction with parenthesis, quotation marks, exclamation points, and question marks:

Further studyThe Copyeditor’s Handbook, 4th edition, Pg. 128

The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition, 6.61–6.67 The Best Punctuation Book, Period, Chapter 4: Colon As of July 1, 2023, Sarah Hawkins Editorial Studio’s policies regarding rescheduling, cancellation, refunds, and editing rounds have been updated. Rescheduling policyShould an author need to reschedule the start date for services, the author will notify Sarah Hawkins Editorial Studio at least one (1) month before the start date. To secure a new start date, the author shall pay a non-refundable rescheduling deposit of 20% of the remaining cost, up to $200. This deposit retains the author’s new start date on the editor’s schedule. Cancellation policyShould an author wish to terminate their agreement before the services are completed, the author will compensate Sarah Hawkins Editorial Studio for services rendered, plus a non-refundable cancellation fee of 20% of the remaining cost, up to $200. Refund policyWhile editing and proofreading will give you a greater chance of success, purchasing a service through Sarah Hawkins Editorial Studio is NOT a guarantee of publication, representation, favorable reviews, website traffic, manuscript requests, or book sales. The goal of Sarah Hawkins Editorial Studio is to provide a satisfactory service for all clients; however, errors may remain in a manuscript after an edit, and accuracy declines when provided an error-riddled manuscript. The editor’s goal is to catch 80 percent of errors while keeping the authorial style and characters’ voices intact. (see Sources below for information regarding error rates in editing) The editor recommends at least one (1) round of copyediting and proofreading by second trusted person to ensure the lowest number of errors prior to publication. If an author determines the services provided did not fit their particular editing needs or were not performed up to the author’s standards, they shall notify the editor about their concerns within thirty (30) days of the author’s receipt of the manuscript delivery or final invoice payment. The editor will make every attempt to address any concerns or identified issues at no cost to the author, and the author will provide any additional information the editor may need to complete their review. The editor will only consider a partial refund of 20% of the total cost, up to $200, when those issues cannot be resolved. Editing RoundsAfter the author responds to suggested queries, the author may send the edited manuscript back to the editor for a second editing round. The author has two rounds available per Agreement, and a round consists of one (1) to three (3) editing passes.* *This is a change from the previous policy of two rounds after the edited manuscript is initially delivered to the author. Where to find my policiesAll of Sarah Hawkins Editorial’s Policies can be found on the Policies page, and they are also outlined in the Editing Agreement provided to potential authors. You may review a copy of the Editing Agreement here. I recommend any author considering collaboration review the Editing Agreement and complete a free 500-word editing sample before signing the Agreement. Exceptions to these policies will be determined on a case-by-case basis. SourcesSarah Hawkins Editorial Studio's goal of 80 percent accuracy rating was determined through the review of the following sources:

According to The Copyeditor’s Handbook, “… 95 percent accuracy is the best a human can do. To pass the certification test administered by Editors Canada, an applicant must score approximately 80 percent or higher. And, as experienced editors know, accuracy declines in an error-riddled manuscript.” In her blog post “6 Myths about Editing,” Crystal at Rabbit with a Red Pen reiterates that 80 percent accuracy of editors. However, please note that on the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading's Website, they state: "Having said that copyeditors can’t make text perfect, it is important that they work to a high standard. Some people will assert that copyeditors should catch a certain percentage of errors, but we don’t believe this is helpful – because of the subjective nature of errors, and also because the copyeditor will be working within other constraints. Excellent work depends not only on the skill of the copyeditor but on the budget and schedule being adequate for the job. Rather than using percentages to express an acceptable (or unacceptable) error rate, it’s better to think in terms of the copyeditor making the text fit for purpose within the limits of their brief. There should be consistency and clarity, and no barriers to the reader understanding the meaning of the text." What's discussed in this post

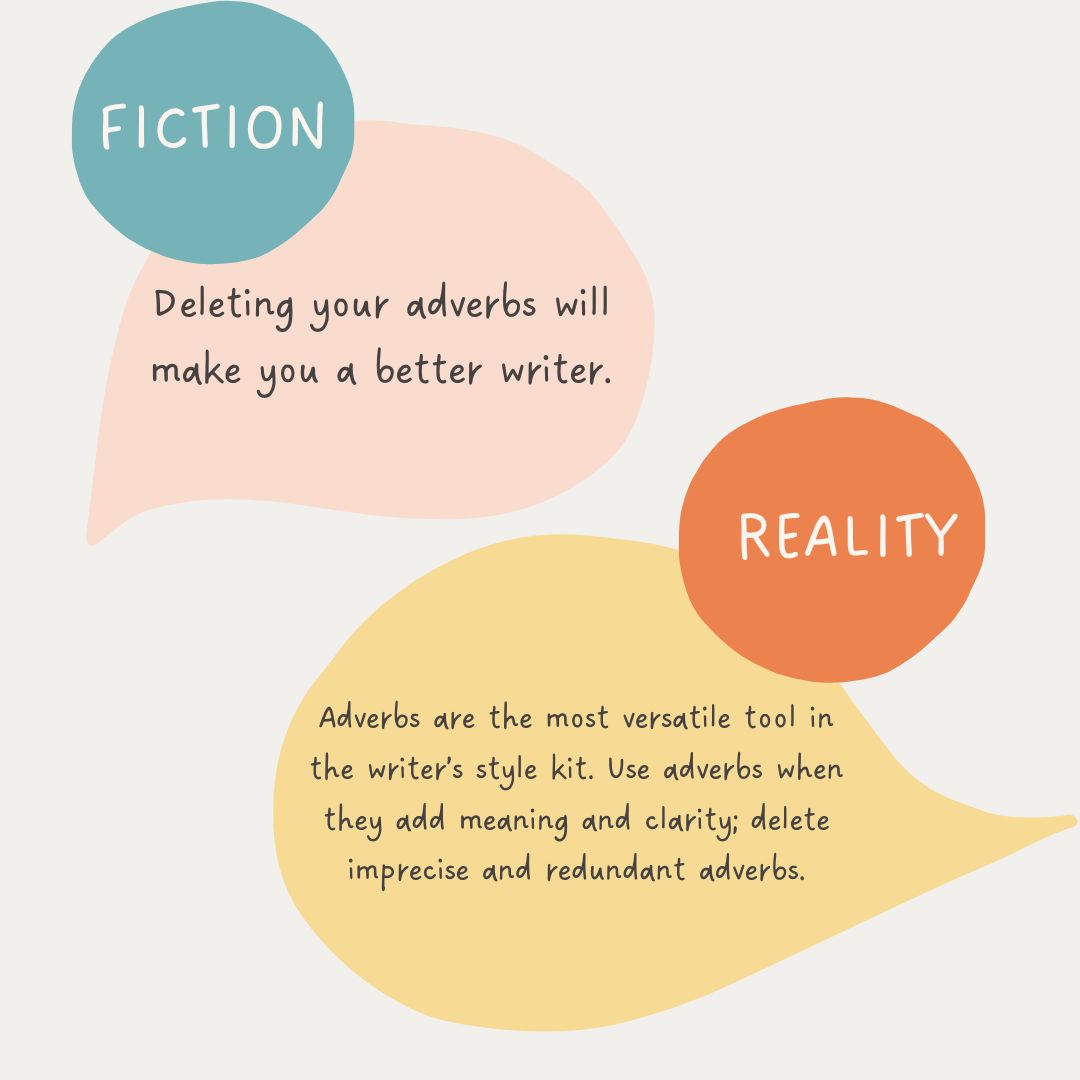

Introduction: powerful adverbials“Easily improve your writing by doing this one thing: delete adverbs.” This is one of the most common pieces of writing advice I see on social media, and I hate it. It’s horrible advice because it’s vague, broad, and a bit moralistic (it sets up those who use adverbs as “bad writers” and those who don’t as “good writers”). You’re not a bad writer if you use adverbs. In fact, even those writers who take that advice to page probably still use them. Adverbials are indeed one of the most powerful tools in a writer’s style kit because they’re so versatile. Not only are there 5 types of adverbials, but each type is movable. This means a writer can play with the position of adverbials until they find the right emphasis, rhythm, and tone for the message they want to convey. What is an adverbial?

(reason), and how often (frequency). Although they are considered a part of the predicate, they can appear nearly anywhere in the sentence. The 5 types of adverbialsThe five main types of adverbs are:

Adverbial degreesSuperlative adverbs compare the quality of an action between at least three persons, groups, or things. Superlative adverbs are sometimes used for emphasis rather than comparison. Placement of adverbialsThe placement of an adverbial can change the emphasis, tone, and meaning of the sentence, so it’s important that you exactly what you want to convey. Generally, you want to place the adverb as near to what it’s modifying as possible to prevent a misreading. Middle adverbials show up within or directly around the verb phrase. They put stress on the verb, but they can also interrupt the flow of the sentence and can slow the reader down. The normal placement of simple and flat adverbs is here, between the auxiliary and principal verbs or following a principal verb. Adverbs that modify words other than verbs should immediately precede the word qualified. She hastily sat on the settee. Ending adverbials are placed after the main clause. They put stress on the adverbial. If the adverbial provides new information, it should be placed here. Adverbs generally follow intransitive verbs. She was sitting on the settee when I walked into the parlor. Signs of ineffective adverbials

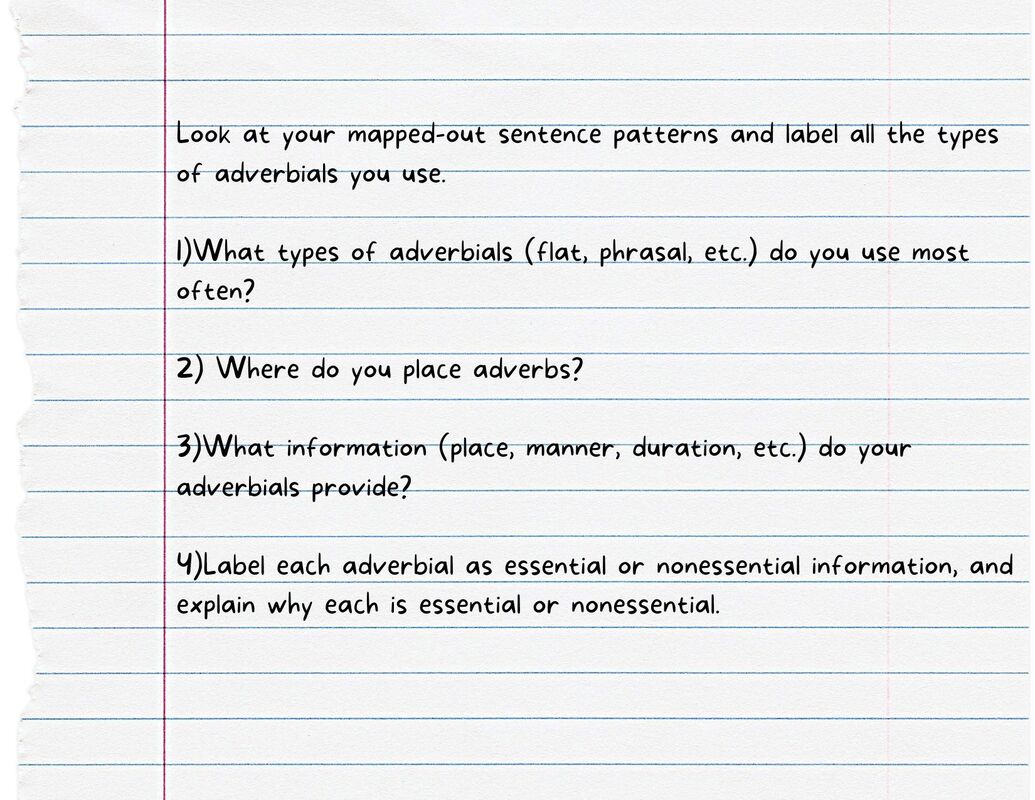

Exercise 4Further studyThe Chicago Manual of Style 5.156–5.171

3 writing myths debunked What's discussed in this post

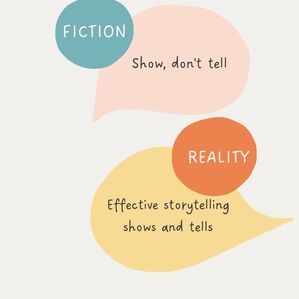

Show, don't tell

detail in the narrative distance and directing the reader’s focus. Since telling is often framed as bad writing, here are some criteria for using telling effectively: Delete your adverbsacknowledge the type of information they find so troublesome. Adverbs provide information about manner, direction, time, duration, or reason. They are focused on simple-and-flat adverbs of manner, which are often adverbs created from an adjective and the derivational suffix -ly (e.g., softly, happily, quickly). And there is some value in wanting to reduce your use of manner adverbs. If there is a verb that conveys both the action and the manner, the adverb is redundant and should be deleted. If the adverb doesn’t add meaning or clarity to the sentence, it’s imprecise and should be deleted.

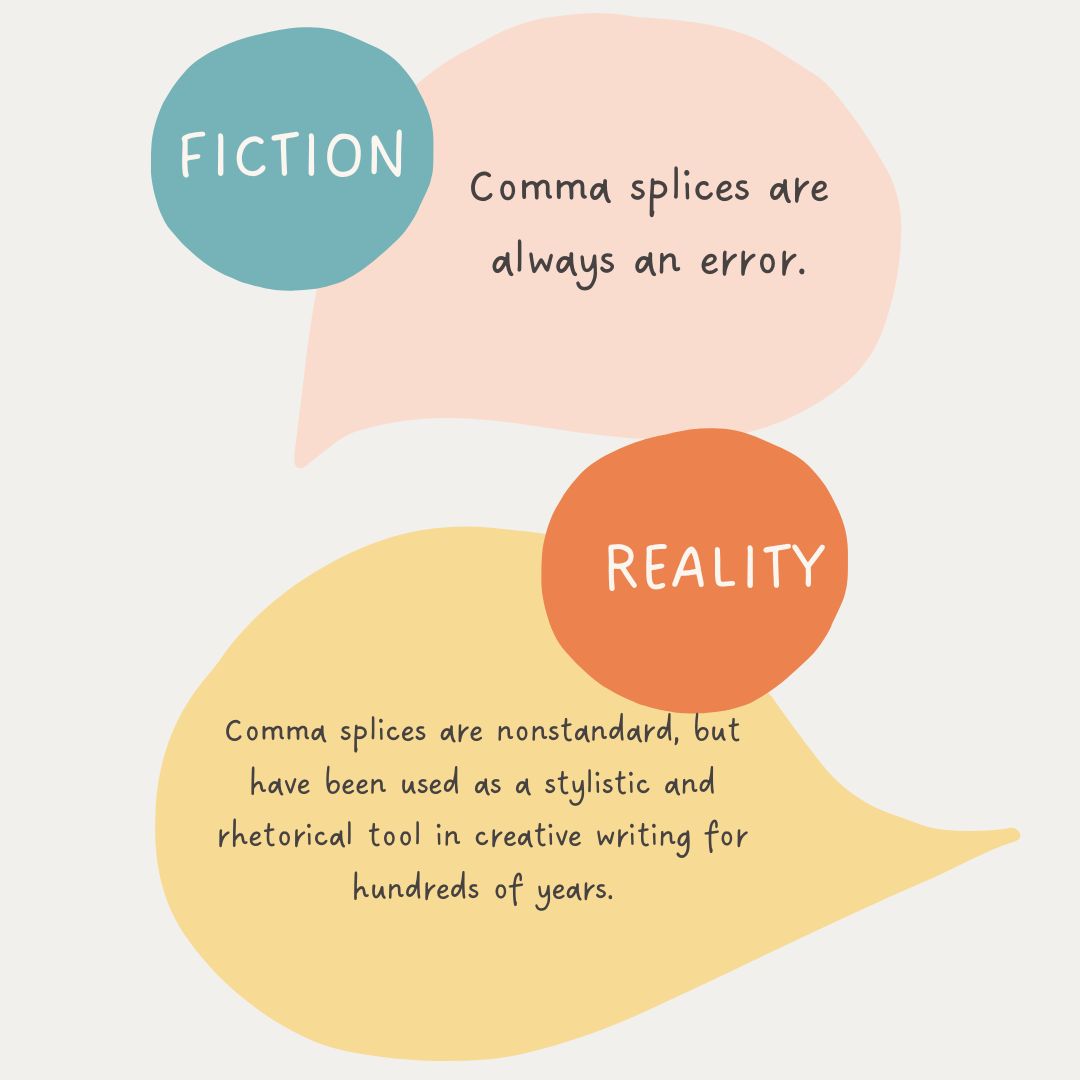

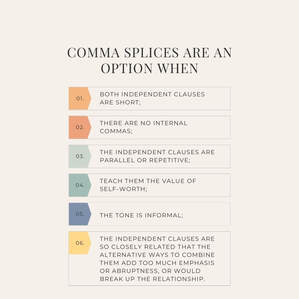

sentence. This is especially true of sentences with intransitive verbs, which take no direct object. If you want to expand I ran, you need to add an adverb or adverbial. So a better way to phrase this advice is: Use adverbs when they add meaning and clarity; delete imprecise and redundant adverbs. Don't use comma splicesI discussed the effective use of the comma splice last fall, but I’ve seen pushback against the use of the commas splice come up again (probably because I’ve advocated for it as a stylistic tool). Yes, the comma splice is nonstandard and most grammar books, therefore, advise against it; but it has been used as a stylistic and rhetorical tool for hundreds of years. Need proof? Dicken’s A Tale of Two Cities opens with a paragraph of comma splices, and my 9th-grade English teacher loved that paragraph so much, she forced us all to memorize it and test us on it.

Finally, several reference books I own—including Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace by Joseph M. Williams and Joseph Bizup, Rhetorical Grammar by Martha Kolln and Loretta Gray, Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, The Copyeditor’s Handbook by Amy Einsohn and Marilyn Schwartz—and The Chicago Manual of Style’s “Fiction+” blog acknowledge the comma splice as an option in creative writing. Comma splices are most effective when:

Self-edit tips

Highlight all the adverbs and verbs in your sentence in two different colors. Analyze: Am I using a lot of the following verbs: linking be, have, make, go, do, get, or take? What kind of adverbs am I using? For comma splices: Many line editors, copyeditors, and proofreaders will automatically correct a comma splice even when it is a part of the author’s style, so the first thing you must do is determine how you use the comma splice, and whether or not you want it as part of your edited style. Ask a trusted reader or your editor to mark comma splices so you can analyze, assess, and revise.

This all helps you learn when you want to stet for style in the future. Stet means “let it stand,” and it’s what authors (and sometimes editors) do when they reject an edit on their manuscript because they think it changes the meaning, rhythm, or tone of a sentence. Make sure you mark anything you stet for style with a comment before you give it or return it to your editor for a final pass. What is a writing myth you've come across on social media? Comment below!Further Study3 ways to use comma splices effectively The Chicago Manual of Style Fiction+ hompage "Comma Splices and Run-on Sentences," The Chicago Manual of Style Fiction+ Using adverbs in fiction – clunk versus clarity “Showing versus telling” in Editing Fiction at Sentence Level by Louise Harnby Oh, the Splices You’ll See!

14 novels editedUnreleased & covers not currently available:

6 Novellas and Vellas edited*Stripped Away and The Daring Adventures of Honoria Porter are ongoing. 15 short fiction pieces editedPlus 12 other short fiction pieces! 3 trainings completed

Thank you!When I began my freelance editing business in 2020, I never dreamed I would have such consistent work! Thank you for giving me a sneak peek at all your stories this year. You are all so talented and impressive, and polishing your manuscripts is the most rewarding work I've done in my adult life. I can't wait to see what is in store for you all in 2023! Happy New Year!What’s discussed in this post

Farther vs. furtherFarther is for literal or physical distance. She ran farther than me.

Therefore, the correct word to describe a character being “unaffected,” is unfazed. She was unfazed by his comment. Breech vs. breachAt thirty-seven weeks, the baby was in a breech position. The verb form of breach means to break open or break through. Therefore, breach is the correct homophone to use. They breached the border. Self-editing tipsWhen dealing with homophones and near-homophones, we need to look at both the words’ meanings and the context to determine which word to use. One way to do this is to highlight the word, right-click, and look up synonyms. If none of the synonyms match the meaning of the word, you're probably using the wrong homophone. However, in the case of further and farther, this way would not be reliable because the first definition of further is farther (English is so fun). So if you have MS Word, a second way to do this is to add the MerriamFetch macro. This is my favorite way to verify spelling and word choice because you can set it up with a keyboard shortcut so that Merriam-Webster is a keystroke away at all times. Here is where you can find the MerriamFetch macro by Paul Beverley. Lastly, if you know what homophones you confuse, make a reference chart! Further readingInstagram, @itssarahhawkinsedits, “Is it I have further to go or I have farther to go?”

The Chicago Manual of Style, “5.250 Good Usage versus common usage.” Editing Macros by Paul Beverley What’s discussed in this post

IntroductionIn the last chapter of the Style Series: Grammar 101 post, we learned all about the 7 basic sentence patterns. These form the core of every sentence. Without them, you cannot have a complete, grammatical sentence, or an independent clause. But you may have noticed that your nouns, verbs, and predicates are more complex. Each part of the independent clause can be expanded, or added onto, to create complexity and interest. This is where phrases and clauses, and subordination and coordination come into play. The difference between a clause and a phraseWhen you look up "clause" and "phrase" in the dictionary, their definitions sound similar. Both are a group of words, but phrases only form a syntactical unit with a single grammatical function (ex. adverbial phrase), and clauses contain a subject and predicate. For example, let’s look at the following sentence: When I walked up to the counter, the barista scanned me from head to toe. The independent clause is the barista scanned me (noun + transitive verb + direct object). But as you can see, I naturally made a complex sentence with two add-ons: When I walked up to the counter, the barista scanned me from head to toe. The first part of the sentence is a clause because it has a subject (I) and a predicate (walked up to the counter). It can easily become a complete sentence by removing the introductory when. The final part of the sentence is a phrase because it has no verb but still forms a grammatical structure, an adverbial. What is CoordinationCoordination occurs when you expand your sentence by linking like grammatical structures with punctuation and/or conjunctions. There are three types of conjunctions:

Ex. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; however, they were terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. We’ll explore this sentence further as we review the types of coordination. Types of CoordinationThere are two main types of coordination: coordination within a sentence, and coordination between sentences. indirect objects (noun phrases), and compound predicates (verb phrases). Let’s look at the intrasentence coordination in the example from above. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; however, they were terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. There is only one example intrasentence coordination in this sentence. The compound subject Milo and Greg uses the coordinating conjunction and to form a noun phrase. Below is the sentence recast to create a compound predicate: Milo and Greg danced and sang, and they were terrible at both, which made us laugh.

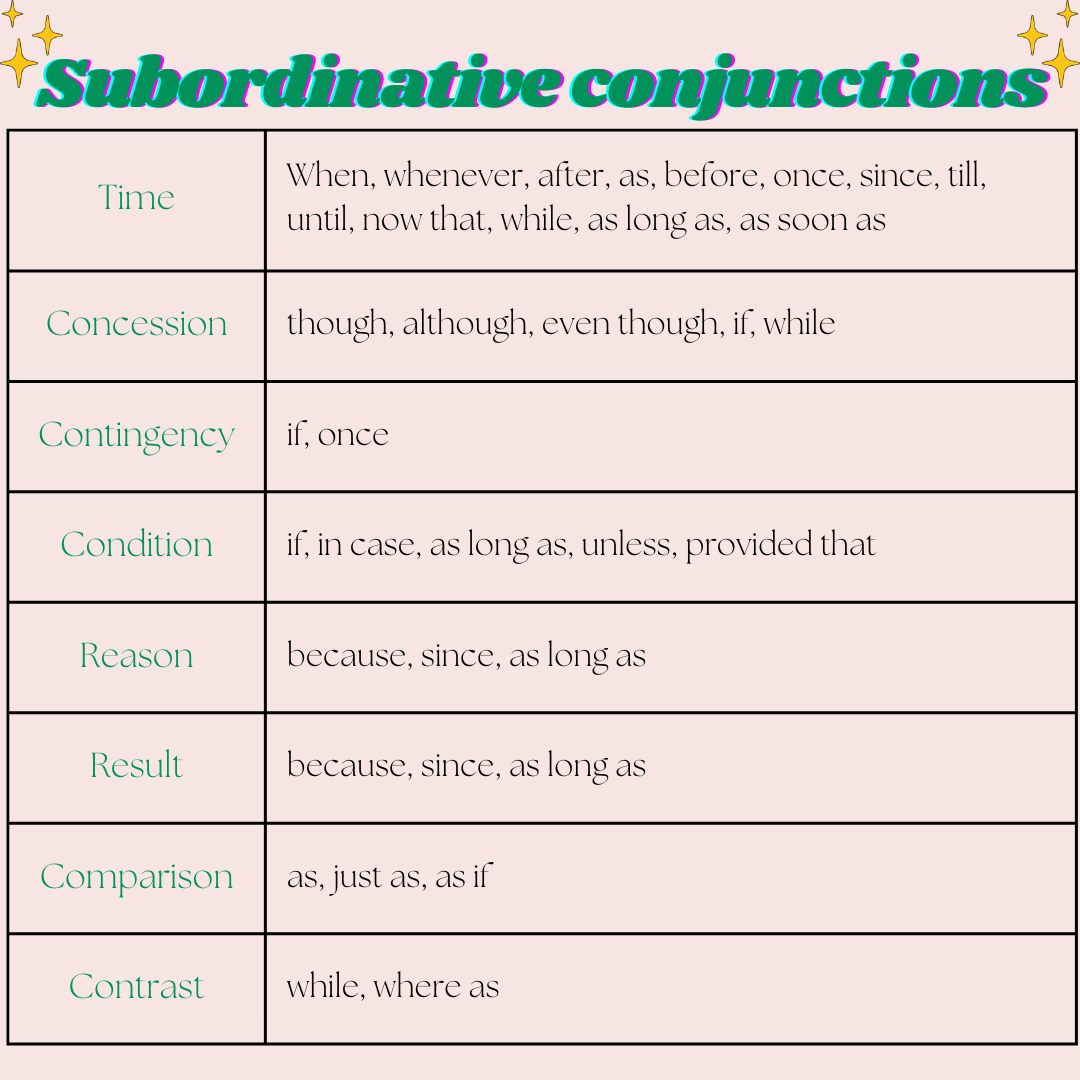

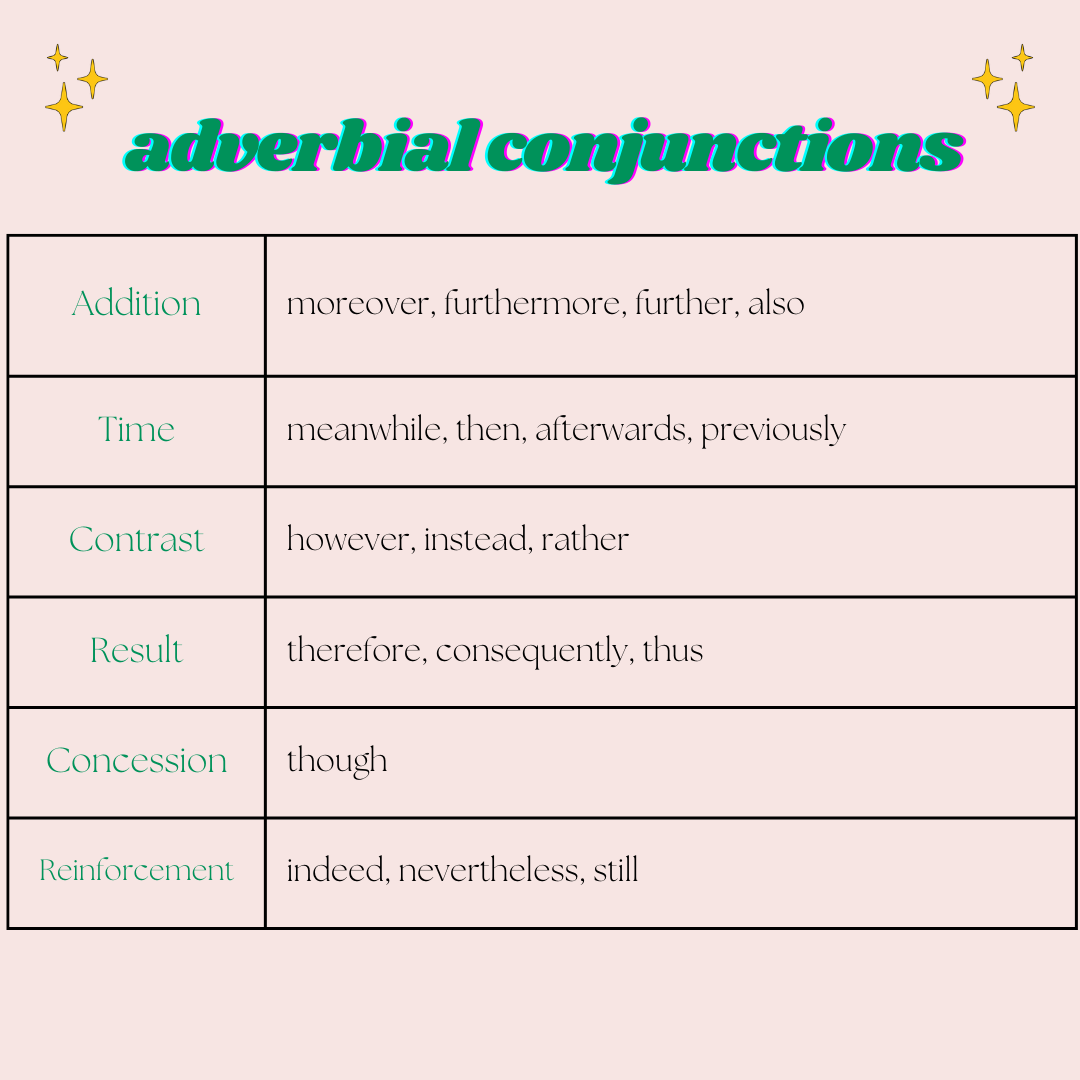

The first type of intersentence coordination uses the correlative conjunction Not only–but also to connect two independent clauses. Notice the Not only clause is an inverted sentence, where the verb comes before the noun, and a different emphasis and rhythm are created. You may have also misidentified this conjunction because but also is split up by they. While not only is always one unit, but also can be together or split up, depending on what you want to emphasize. See how the emphasis changes when new move the also: The second type of intersentence coordination is ; however. However is an adverbial conjunction, and in its current position, it requires a semicolon to prevent a run-on sentence. Like correlative conjunctions, adverbial conjunctions have flexibility. They can move them throughout the sentence to change the emphasis. In most cases, you’ll want to enclose the adverbial conjunction with a pair of commas or a semicolon and a comma. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; they were, however, terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; they were terrible at both, however, and we all had a good laugh. The third type of intersentence coordination is the coordinating conjunction and. (If but wasn’t part of a correlative conjunction, it would be a coordinating conjunction too!) This is probably the simplest form of intersentence coordination, and the one writers, no matter their level of expertise, are most familiar with. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; however, they were terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. With some exceptions, a comma comes before the coordinating conjunction when it is connecting two complete sentences. Types of SubordinationYou create subordination through dependent (subordinate) clauses. These clauses begin with a subordinating conjunction and include a subject and predicate. There 8 types of subordinating conjunctions:

Types of Subordination There are three types of subordination: adverbial, adjectival, and nominal. But each of these types of subordination has subtypes. Adverbial clauses Like other adverbials, an adverbial clause modifies a verb phrase. They can be tricky to identify because adverbials are movable, so they can appear anywhere in the sentence, depending on what the author wants to emphasize. Therefore, a good clue that you’re working with an adverbial is that you can move it. I used an adverbial introductory clause in my coffeehouse sentence to tell the reader when the barista scanned me: When I walked up to the counter, the barista scanned me from head to toe.

A variation of the adverbial clause is the elliptical clause, in which something is deleted. The elliptical clause is always introduced by either while or when. When you use the elliptical clause, the subject of the main clause is always the understood subject of the adverbial as well. Adjectival clauses Adjectival clauses, also known as relative clauses, are clauses that modify a noun phrase, which includes subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, subject complements, complements, and objects of prepositional phrases. They are introduced by a relative pronoun (that, who, or which) or a relative adverb (where, when, or why). Let’s add an adjectival clause to the barista sentence as an example: When I walked up to the counter, the barista who was steaming milk scanned me from head to toe. There is often more than one barista behind the counter, so by adding the adjectival clause to the sentence, we specify which barista scanned me. We also add a little suspense because of what the barista is doing when they scan me. It hints at their intention (to check me out), and it hints at what may come—some romcom meet-cute shenanigans. Sometimes adjectival clauses that start with which don’t refer to any specific noun, but instead refer to the whole main clause. These are called broad reference clauses. When I walked up to the counter, the barista who was steaming milk scanned me from head to toe, which thrilled me.

In the case of When I walked up to the counter, the barista who was steaming milk scanned me from head to toe, the adjectival clause provides identifying information and therefore no comma is necessary. Nominal clauses Nominal clauses are clauses that fill noun phrase positions. Essentially, if the clause functions as a noun, you have a nominal clause. Two of the most common types of nominal clauses are the nominalizer and the interrogative. A nominalizer is introduced by the relative pronoun that and fills the place of direct objects, subjects, or introduces indirect speech. I suspect that the barista liked what she saw. That the barista over steamed the milk proves she liked what she saw. She said that the barista scanned me from head to toe when I walked up to the counter.

The other type common type of nominal clause is introduced by an interrogative (who, what, when, where, why, which, or how), so I’m going to call it an interrogative nominal clause. I wondered why she was checking me out. Who I was going on a date with was kept secret. I didn’t know anything about how the rules of football work. My main question, why she was checking me out, can only be answered by the barista. While that can often be omitted in a nominalizer, the introductory interrogative word cannot be omitted from the clause. Exercise 3Further ReadingChapter 4, “Coordination and Subordination” in Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects, 6th ed., by Martha Kolln and Lorette Gray

Pages 157–166, 180–185, 201–202, “Coordination and Subordination” in Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects, 6th ed., by Martha Kolln and Lorette Gray “What is a Subordinate Clause,” Grammar Girl blog and podcast Style Series, Grammar 101: The seven basic sentence patterns Style Series: What is a Writing Style |

AuthorSarah Hawkins is a geek for the written word. She's an author and freelance editor who seeks to promote and uplift the authors around her. Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed