What’s discussed in this post

Farther vs. furtherFarther is for literal or physical distance. She ran farther than me.

Therefore, the correct word to describe a character being “unaffected,” is unfazed. She was unfazed by his comment. Breech vs. breachAt thirty-seven weeks, the baby was in a breech position. The verb form of breach means to break open or break through. Therefore, breach is the correct homophone to use. They breached the border. Self-editing tipsWhen dealing with homophones and near-homophones, we need to look at both the words’ meanings and the context to determine which word to use. One way to do this is to highlight the word, right-click, and look up synonyms. If none of the synonyms match the meaning of the word, you're probably using the wrong homophone. However, in the case of further and farther, this way would not be reliable because the first definition of further is farther (English is so fun). So if you have MS Word, a second way to do this is to add the MerriamFetch macro. This is my favorite way to verify spelling and word choice because you can set it up with a keyboard shortcut so that Merriam-Webster is a keystroke away at all times. Here is where you can find the MerriamFetch macro by Paul Beverley. Lastly, if you know what homophones you confuse, make a reference chart! Further readingInstagram, @itssarahhawkinsedits, “Is it I have further to go or I have farther to go?”

The Chicago Manual of Style, “5.250 Good Usage versus common usage.” Editing Macros by Paul Beverley

0 Comments

What's covered in this post

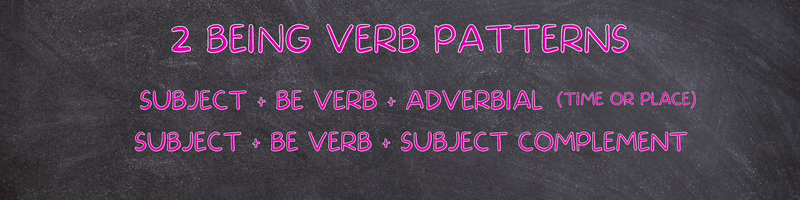

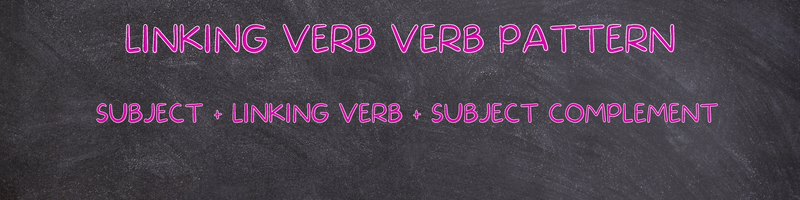

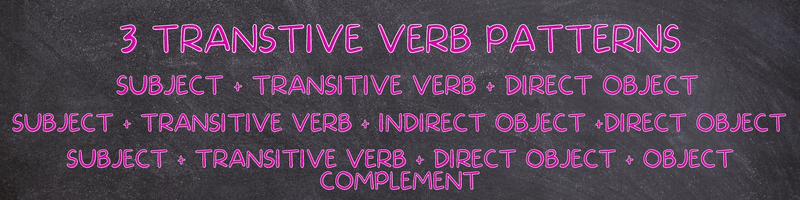

IntroductionYou need a good foundation in grammar to curate and intentionally use your style. So, we are embarking on the Grammar 101 section of the Style Series. This week we’re going to learn all about the 7 basic sentence patterns. Be patterns Be patterns involve any verbs derived from the infinitive “to be.” They include is, am, are, were, was, been, and being. Being Verbs have a bad reputation as weak verbs, but when used correctly, they can be powerful. There are two basic sentence patterns that use being verbs: In the first pattern, the being verb is followed by an adverbial . An adverbial is any structure that modifies a verb. But in this pattern, it is usually an adverbial of time or place, or answers the questions When? or Where? Example: She is in the chair. She + is + in the chair = Subject + Be + Place Adverbial (where) In the second pattern, the being verb is followed by a subject complement, which is either an adjective or a noun phrase called a referent. Referents rename the subject while adjectives describe the subject. Examples: The playroom is a mess. The playroom + is + a mess = Subject + Be + Referent The playroom is messy. The playroom + is + messy. = Subject + Be + Adjective Linking verb patternLinking verbs are all verbs other than “to be” that are completed by a subject complement, such as taste, smell, feel, become, remain, look, appear, seem, and prove. There is only one basic sentence pattern that utilizes linking verbs: But the linking verbs still serve different functions. The sensory-based linking verbs (taste, smell, etc.) usually link the subject to an adjective. Example: This book smells amazing. This book + smells + amazing = Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Other linking verbs, such as become and remain, link a noun to a referent. Example: This house remains a mess. This house + remains + a mess = Subject + Linking Verb + Referent Intransitive verb patternAn intransitive verb is an action verb (also considered a “strong” verb) that doesn’t take a direct object, such as ran, jump, laugh, and bark. Therefore, the intransitive verb pattern is the simplest pattern. Example: The T-rex ran. The T-rex + ran = Subject + Intransitive Verb Transitive verb patternsLike intransitive verbs, transitive verbs are action verbs. But transitive verbs take a direct object, which is a noun phrase that answers the question of What? or Whom? There are three basic sentence patterns that use transitive verbs: In the first pattern, the transitive verb and direct object complete each other. You don’t need anything else to understand the core sentence. Example: We eat pizza. We + eat + pizza = Subject + Transitive Verb + Direct Object In the second pattern, an indirect object completes the meaning of the sentence. An indirect object refers to whatever receives the direct object, or whomever the action is performed for. Example: TikTok gave many writers a community. TikTok + gave + many writers + a community = Subject + Transitive Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object In the third pattern, an object complement follows the direct object. Like a subject complement, an object complement is a noun or phrase. But an object complement describes the direct object. Example: My son calls quesadillas piñatas. My son + calls + quesadillas + piñatas = Subject + Transitive Verb + Direct Object + Object Complement Exercise 2: Identifying Your Sentence PatternsWhat's covered in this post

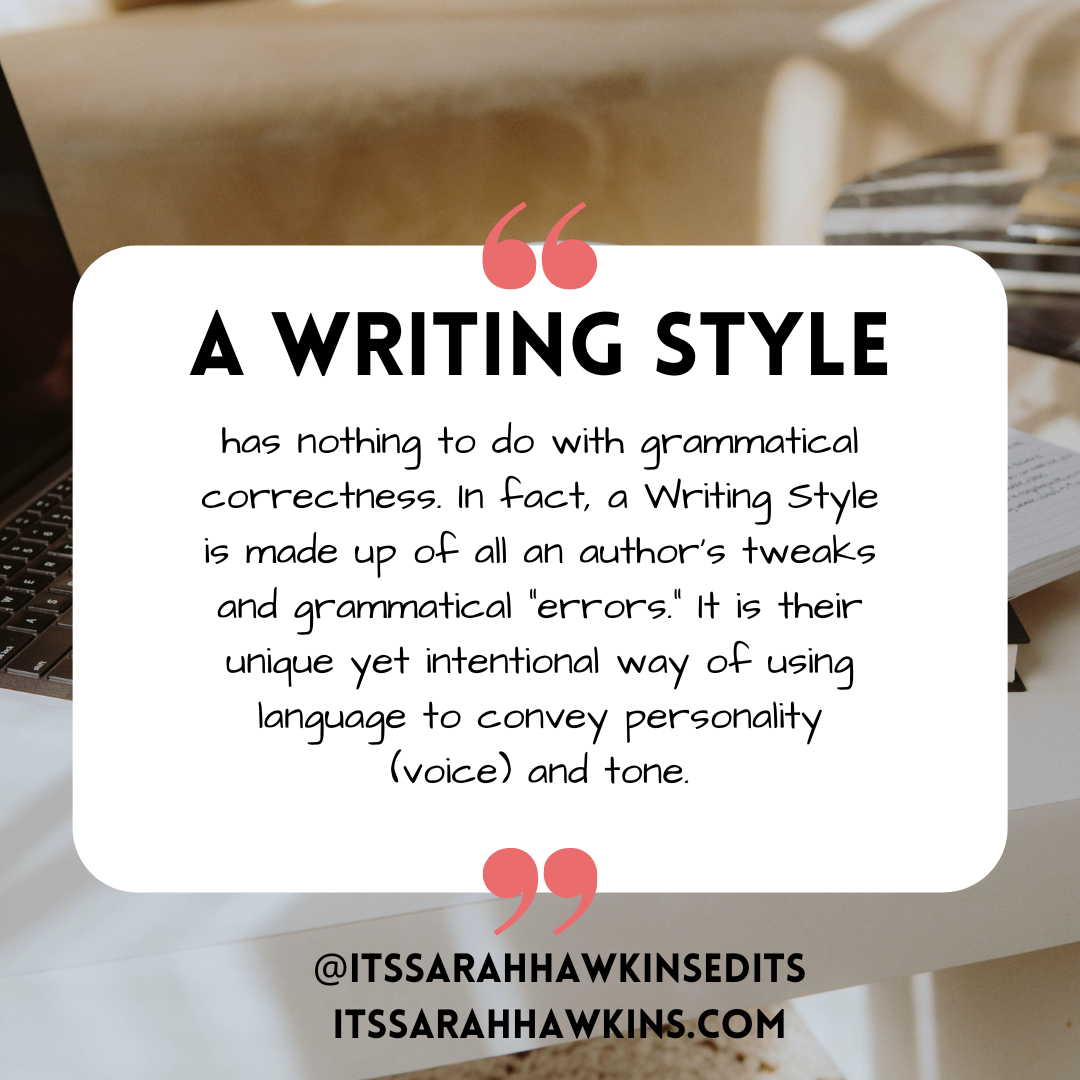

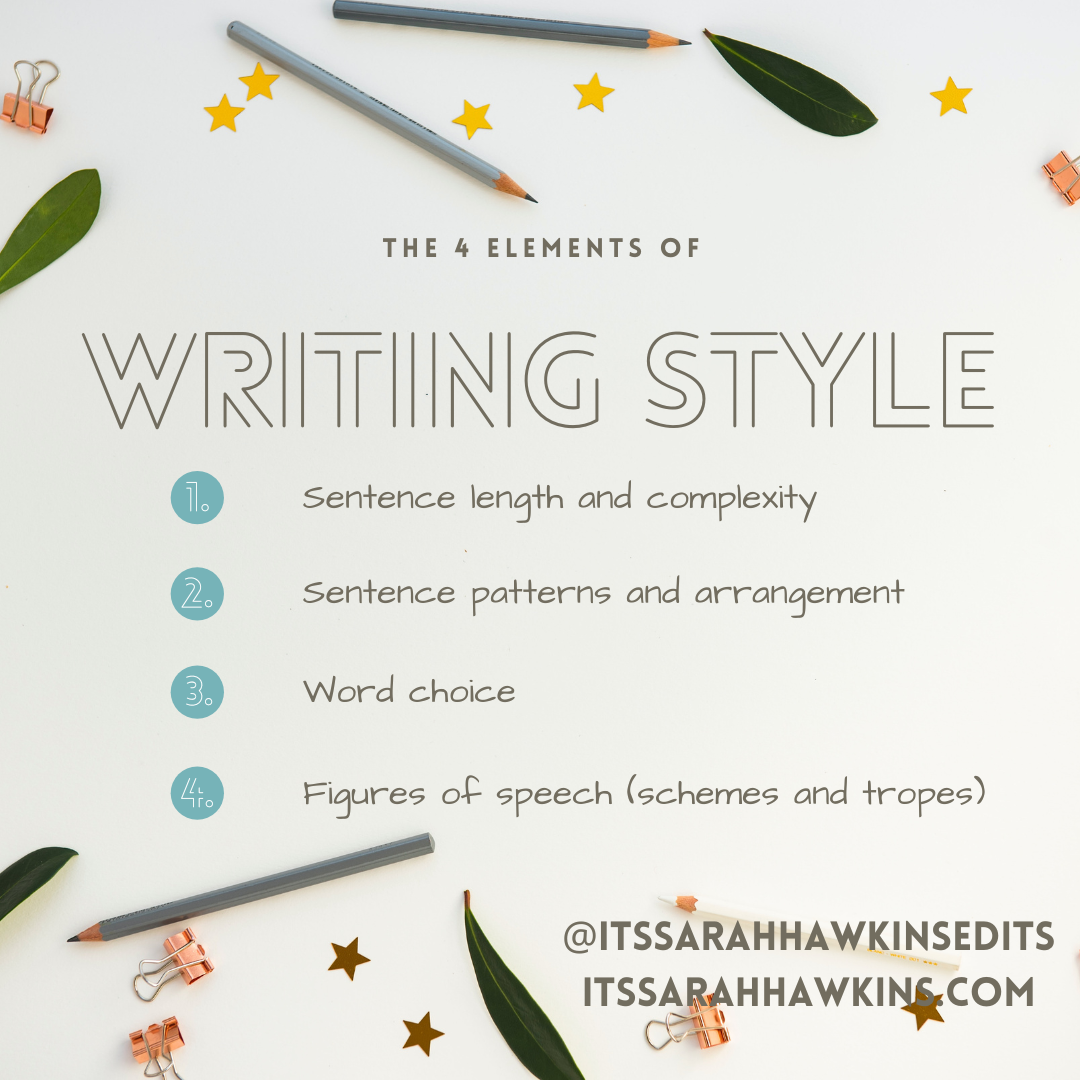

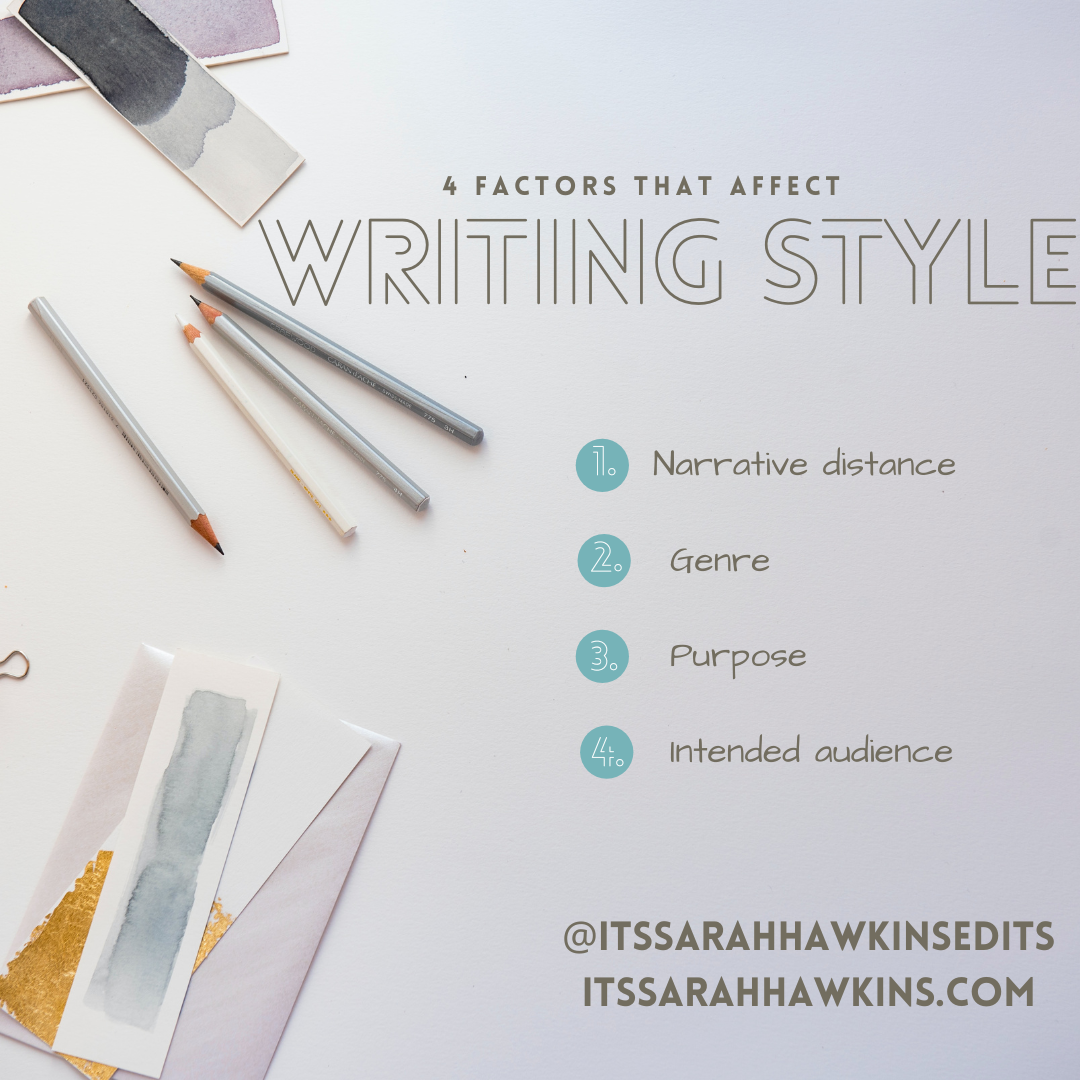

What is writing style?This is because Writing Style has more to do with rhetoric than grammar. Rhetoric is how an author uses diction, sentence structure, punctuation, and sentence and paragraph arrangement to convey emotion, evoke empathy, form a logical path of thought, and create narrators and characters that readers will trust. The 4 Elements of StyleWhile an author’s style may vary from project to project, it will remain consistent and recognizable overall. An author creates their writing style through the following elements: (1) Sentence length and complexity is the most basic aspect of style, in that it is the most recognizable. When you open a book or look at your writing, you can tell at a glance whether you use shorter or longer sentences, and simple or more complex sentences. The punctuation gives it away. More commas, dashes, parentheses, and semicolons are an indication you use longer, more complex sentences. You'll see a lot of ending punctuation marks (periods, exclamation points, question marks) if you use shorter, more simple sentences. You're going to have a variety of both, but you will notice that you're more likely to use a complex over a simple sentence. (3) Word choice focuses not only on the connotation and denotation but also on the word size and how you create compounds. (4) Favorite figures of speech (schemes and tropes) are how you add embellishment and decorate your prose, although that is not their sole function. Schemes involve the transference of word order, and tropes involve the transference of meaning. We'll be discussing the different types of schemes and tropes later in this series, but some examples of schemes include polysyndeton (many conjunctions), parallelism, and elision. Some examples of tropes are: metaphor, puns, and personification. 4 Factors that affect Style While the above four elements remain consistent overall and therefore recognizable, your Writing Style varies from project to project through the following four factors:

Exercise 1: Sentence length and complexityWhat's discussed in this post

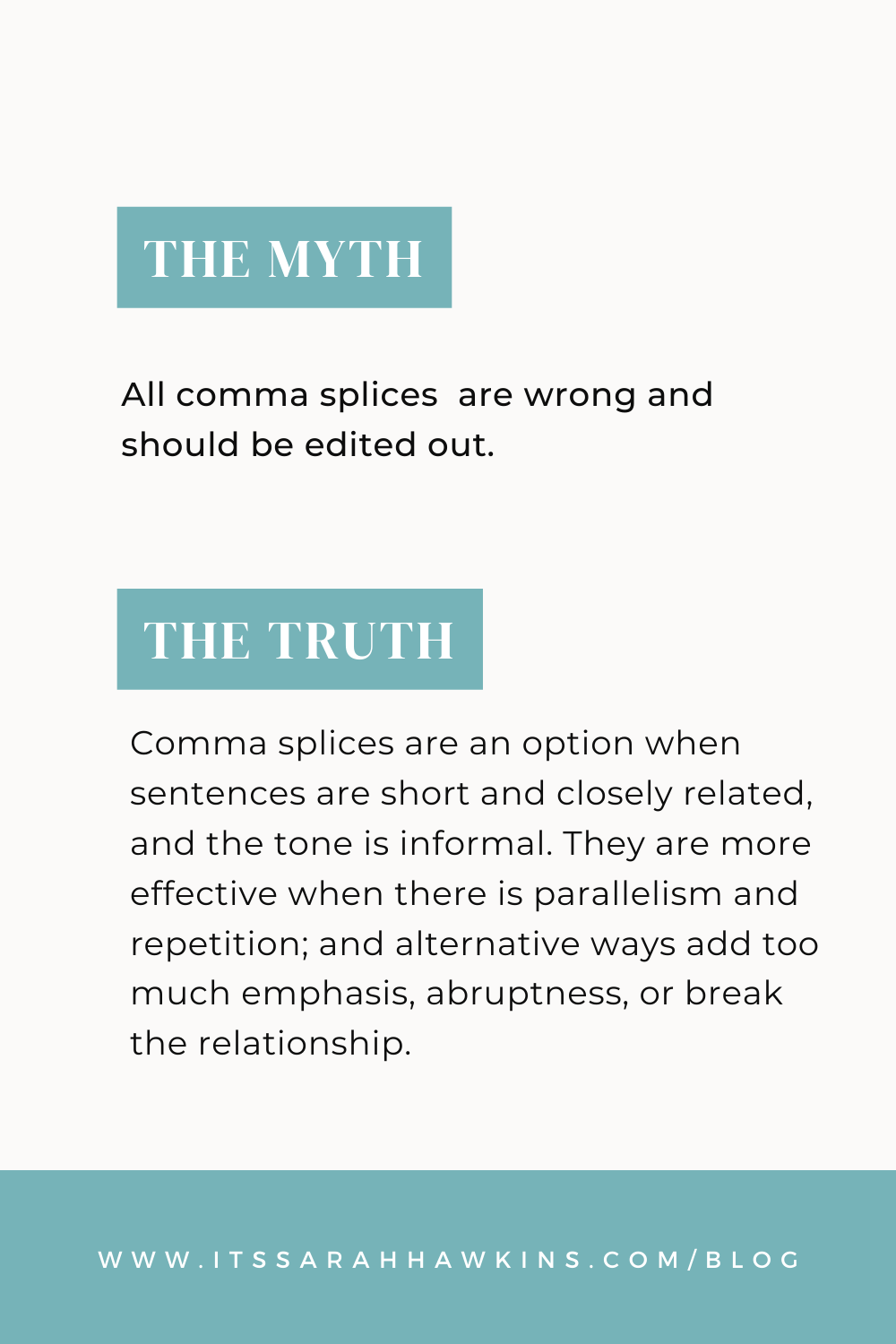

What is a comma splice?A comma splice occurs when two grammatically correct and complete sentences (independent clauses) are joined (or spliced together) by a comma. Here it is in a formula: Comma splice = [Independent clause] , [Independent clause]. Example: It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . . (From A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens) Is a comma splice ever correct?Comma splices are considered nonstandard, but CMOS Fiction+ Shop Talk writer Russell Harper and the infamous The Elements of Style authors Strunk & White both point out that a comma splice isn’t always an error. It’s an option, but it should only be used when it is the best option. How do you know if it’s the best option? That depends on context, tone, and intended emphasis. In general, a comma splice is an option when:

Since comma splices can be viewed as an error by discerning readers, it needs to be used sparingly and with obvious intention. Below, we are going to talk about three ways to use a comma splice intentionally through asyndeton. Asyndeton and comma splicesAsyndeton is a scheme of omission in which you leave out, or omit, conjunctions between coordinate words, phrases, and clauses. Often, you use a comma to indicate the elision, which is allowable per CMOS 6.54 (“Commas to indicate elision”). When you utilize asyndeton between independent clauses, you create comma splices. Asyndeton between independent clauses is most effective you need to create a hurried rhythm, show dichotomy, or show an emotional reaction. Comma splices to create a hurried rhythmHere’s a famous sentence popularly attributed to Julius Caesar: I came, I saw, I conquered. This sentence checks most of the boxes in the guidelines outlined above: The sentences are short and closely related, they have parallel structure, but since we don’t have context, the tone is vague. The lack of conjunctions here allows us to say the entire sentence in one, short breath, which gives us the impression that not only was Caesar successful, but the three actions were done in such quick succession and with such ease that he didn’t even break a sweat. A less experienced (or less brave) editor would edit this sentence according to current standards and conventions, but we would lose a lot of the meaning. I came; I saw; I conquered. I came. I saw. I conquered. I came, I saw, and I conquered. The semicolons and periods (also known as hard stops) still create a hurried rhythm, but there is too much breath, too much distance between the actions. They also read a little sarcastic in tone, like the speaker is annoyed and talking down to the listener. The conventional use of “and,” doesn’t have this tone, but the hurried rhythm is lost. In all three conventionally combined sentences, the three actions feel more laborious. He broke a sweat completing all three tasks. This balance between tone, rhythm, and convention is something I had to consider recently. My client Stephanie K. Clemens uses comma splices to create asyndeton in Stripped Away, her political fantasy Kindle Vella, to create a hurried rhythm:

The break in parallel structure with the third clause, nothing happened, also serves the sentence. Breaking the repeating structure creates a tone of relief and confusion, which is precisely how Kennara feels. Since simultaneity and tone are essential to the meaning of the sentence, I kept the comma splices/asyndeton, explained why in a comment, and told Stephanie how awesome she is. Comma splices to show a dichotomyDichotomy is “a division between two especially mutually exclusive or contradictory groups or entites.” The most famous display of comma splices and dichotomy is the first paragraph in A Tale of Two Cities: It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way . . .

It grounds the reader in the historical setting of 1775, it’s setting up the main conflict of the book between the aristocratic class and the impoverished. The string of comma splices weaves together these two goals, showing how tangled the conflicts and setting are. If we separate the clauses and recast them conventionally, we lose the entanglement of conflicts and worlds. My client Jesse Harvey used comma splices and dichotomy recent in her book, Uthraith Tauristar: Book Two of The Dark Stellar Legacy: The first sentence utilizes a compound predicate, which highlights subject complement inseparable and the verb phrase forever entwined. Anything other than a simple and would disrupt the closeness of that relationship between the two worlds. The second sentence continues describing this relationship. And it stands out. Never touching, always together has both fragments and a comma splice. The two fragments contradict, just like the worlds contradict—they are the tangible world, and an invisible world called the aether—and the comma splice serves as a bridge between the dichotomic relationship and existence. It also sets up the last two sentences, which show the two characters' relationship to these worlds. We finally get two short, simple sentences that are repetitive. A comma splice would've been an option here if it weren't for the context. But separating the two subject compliments into two sentences adds the forceful staccato tone Jesse was going for in this training scene, and it also sets up the two roles the characters play between the two worlds. If I had edited the comma splice in the second sentence to a more conventional method, we would've not only lost the meaning in the second sentence but also the meanings in the rhythms of the surrounding sentences. Super cool, right? Comma splices to create an emotional reactionWe talked a little about this with the example from Stephanie K. Clemen’s Stripped Away: The combination of the comma splice and structural change in the last clause created a sense of relief for the POV character Kennara. My client Arabella K. Federico also used the rhythm of a comma splice to show an emotional reaction in her character Kara in The Mark of Chaos and Creation: The tone is informal—these are Kara's thoughts, only heard by her and the reader—and the clauses also hit the marks of being intimately related, short, and there's even some repetition of sounds in the interjections (the repetition of S in Sure, I suppose) and in the prepositional phrases (at some point, in some way), which tie the clauses even closer together. The comma splices here serve to show the winding thoughts of Kara in an introspective moment. They create a soft tone, which contrasts headstrong and intense, and feel almost lonely. It also highlights one of the main struggles Kara has throughout the book: the longing to belong and the constant feeling of being left out. It just breaks your heart, doesn’t it? If I edited this conventionally, the tone would’ve shifted dramatically: Sure, I can be headstrong and intense sometimes. I suppose. But it’s like at some point, in some way, everyone leaves me. With the conventional structure, we get more of a pointed staccato, which conveys some incredulity of the judgment that Kara's headstrong and intense sometimes. That’s not what Arabella wanted to convey. Kara already believes these two things are true. The doubt Kara has is whether she is capable of being loved unconditionally. So, we’ve lost that expression of her core belief and true doubt. We’ve also lost the winding rhythm and the softness, which adds to the loneliness and doubt Kara feels and allows the reader to feel them with her. Sometimes nonconventional sentences are the best sentences. Another excellent way to show an emotional reaction with a comma splice is to break the rhythm of a sentence. Unfortunately, I don't currently have an example for this, so if you find out, let me know! Stylistic ConsiderationsEven for the savviest readers, comma splices can be jarring, and they can look like an error to more casual readers, so it is understandable if you’d prefer to avoid them in your writing style. But I wouldn’t discount them completely. Comma splices are voicey and add character to dialogue and narration. Therefore, you may also stipulate that comma splices are only allowable for certain characters, or in dialogue, thought, or free indirect discourse. Whatever the case, make sure you tell your editor your comma splice preferences; they’ll know the best way to edit out the asyndeton while maintaining as much rhythm and meaning as possible. Further Reading

What's discussed in this post

IntroductionWelcome to Editor’s roundup, a monthly post of common edits I’ve made in the last month. This month, we’re discussing 3 compounds that authors commonly mix up, and I’ll give you some tips on how to self-edit for word compounds.

Door frame or doorframe?We’ll start with an easy one. Often, I see authors split doorframe into 2 words, and I’ve even caught myself splitting the compound in my own writing! Merriam-Webster says doorframe is the correct spelling, so I looked into why we have a tendency to split the word. According to the Google Books Ngram Viewer, which checks how words and phrases are used over time, doorframe became the more common spelling in the 2010s. The use of door frame tapered off in 2013, and the use of doorframe peaked in 2017. While door frame is still in use, a quick google search for entries of door frame yields results for doorframe in Merriam-Webster, Cambridge, Dictionary.com, and others, so I would stick to the one-word version. On to or onto?One of the fun things about being an editor is that I second-guess every grammatical rule I know, and then I end up down the rabbit hole. Along with lay vs. lie conjugations, I research onto vs. on to regularly, because if you mix them up, you can change the meaning of your sentence. To know whether you need to use onto or on to, you need to know 4 things. 1.The first thing to know is that the confusion with onto and on to we’re discussing here lies with using onto and on to as prepositions of direction. 2.The second thing to know is that when you use on to, you’re actually using two distinct prepositions of direction: on and to. So, you need to look at these two words individually to see if they both fit the context.

Therefore, you’d only use the prepositions on and to together when you’re describing an object moving toward a destination and into a position. Often, you’re working with a verbal phrase (moved on) and–or an infinitive phrase (to become) when you use on to. She went on to become a bestselling author. (The object she moved toward and into the position of becoming a bestselling author.) They led them on to the upper landing. (The object them was led toward the position of the upper landing.) She moved on to her next lover so fast. (The object she moved toward and into the position of a new lover.) 3.4.The fourth thing to know is that onto and on are interchangeable. So, a good trick to know if you should onto instead of on to is to drop the to. If you drop to without any meaning changing, you can use onto. I set my phone onto the charger and I set my phone on the charger mean the same thing, but I set my phone on the charger sounds better. Compounds beginning with halfHalf can precede verbs, nouns, and adjectives to create compound words. Those grammatical functions determine whether the compound is one word or two. According to The Chicago Manual of Style, the following general rules apply:

There are two major exceptions to these rules:

Self-editing tipsEditing for word compounds can be tricky. Spellcheck will often not recognize if a compound should be two words, one word, or hyphenated. Using a grammar check like Grammarly (although I think you need the premium version) or ProWritingAid can help you eliminate a lot of needless two-word compounds. Additionally, if you edit in Word, you can install a macro that will enable to you look up the word in Merriam-Webster with a couple of clicks. Here are some final tips:

Finally, as you learn which compounds you tend to mix up, make a Find+Replace list for future reference. Further readingGoogle Books Ngram View: doorframe and door frame

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “onto,” accessed September 25, 2022, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/onto. The Chicago Manual of Style 7.89 “Using word macros for editing,” Rabbit with a Red Pen As an author, one of the most important things you can learn is how to describe and practice your unique writing style. This not only helps you use your writing style more intentionally, but it also enables you to discuss your choices with your editor. So beginning in June, I'm going to post a series on Writing Style. What you'll learn in this series

Each post will include a breakdown of the week's topic, a link to my TikTok, and an exercise. Currently, I'm planning on the exercises to build off one another. The goal is that, at the end of the series, you'll understand your writing style and be able to describe it to others.

|

AuthorSarah Hawkins is a geek for the written word. She's an author and freelance editor who seeks to promote and uplift the authors around her. Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed