What's discussed in this post

What is cohesion and why is it important?

When reader expectation is not met, the narrative may read awkwardly, causing the reader’s concentration to break briefly or the reader to backtrack to glean meaning out of what they just read. This disrupts the reader’s immersion and gives them the opportunity to put down your book! This guide explains how to meet reader expectation at the sentence level with the known-new contract, repetition, and parallelism, so you can revise your sentences for cohesion with confidence. The known-new contractOut of the 3 techniques used to create cohesion, the known-new contract is the most important because it’s how the reader learns new information: by connecting it to what they already know. If you struggle with meeting the known-new contract, your sentences may provide new information consecutively, creating a choppy, disconnected flow. To understand this concept, we need to go over how sentences present information:

Starting with a simpler concept of what the reader already knows de-emphasizes it and allows the reader to focus and understand the new information. The new information should be presented in the predicate, where the natural emphasis is, because it allows the reader to retain more complex information and carry it onto the next sentence.

This sentence couplet comes in the scene right after the protagonist, Icelyn’s pet mini-dragon (Ember) had gone missing, sending Icelyn into a depressed panic. Since the reader would already have that in the foreground of their mind, Clemens begins the sentence with Ember finding her way home yesterday and ends with how Icelyn feels today about it, was such a relief it made today feel brighter, which is new information to the reader. In this case, the known-new contract also has a cause-effect structure. Clemens uses cause-effect to connect the first sentence to the second. The effect of Icelyn Humming a winter tune isn’t new information because it is caused by and exemplifies Icelyn’s relief making the day feel brighter, and those emotions are pulled through and motivate Icelyn’s actions in the rest of the sentence. RepetitionThis may seem like a promotion for redundancy, but there’s a major difference between redundancy created through repetition and repetition as lexical cohesion. When repetition is used as a cohesive tool, it acts as a link between sentences. It’s the known in the known-new contract, allowing the reader to focus on the new information, the purpose of the sentence. Repetition only becomes redundant when it has no purpose. Additionally, as stated above, lexical cohesion isn’t only the repetition of words and phrases; it includes the use of synonyms and related words, such as pronouns. Using pronouns is one of the easiest ways to create lexical cohesion because the subject or direct object of one sentence can be the subject of the next, yet they still add variety. Here’s an example of lexical cohesion using pronouns from my work-in-progress, Girls to the Front: We set down the desk in the main room, and I greet Nana. She sits in her usual house dress on the living room couch, watching Murder, She Wrote reruns. The direct object of the sentence I greet Nana sets the reader’s expectation to see Nana in the next sentence. Since Nana is in the foreground of the reader’s consciousness, the use of the pronoun she links two sentences together naturally, and the reader’s expectations are met. A more advanced way to create lexical cohesion is to use a scheme of repetition. A scheme is a structure used to convey meaning. Schemes of repetition include isocolon, anaphora, alliteration, assonance, epistrophe, epanalepsis, anadiplosis, antimetabole, and polyptoton. (I’m going to talk about these in a future post. Stay tuned!) ParallelismParallelism becomes a cohesive device when it’s used to connect sentences and paragraphs by creating an echo structure across them. When you echo a structure from one sentence to another (or one paragraph to another), you remind the reader what should be in the foreground of their mind. This adds intensity and drama. Here’s an example from Girls to the Front: Over the last few years, the church transformed the old school gym into an all-in-one kids entertainment center, with a set of trampolines, a video game setup, and an enclosed, padded play area (for the littlest kids) on the left; and an obstacle course made of ropes, beams, and climbing structures on the right. Here, I use parallel structures to concisely describe a setting. A set of trampolines, a video game setup, and an enclosed, padded area (for the littlest kids) and an obstacle course made of ropes, beams, and climbing structures both consist of three parallel noun phrases. The parallel prepositional phrases on the left and on the right connect the two descriptions to create one image. Finally, parallelism can also be used in the scheme antithesis, which is a comparison of contrasting ideas. An example of parallelism used in antithesis is Neil Armstrong’s famous “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Quick tipsHere are some quick tips based on what we’ve learned in this post:

Further studyStyle and Statement by Edward P.J. Corbett and Robert J. Connors

Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects by Martha Kolln and Loretta Gray Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace by Joseph M. Williams and Joseph Bizup

0 Comments

What’s discussed in this post

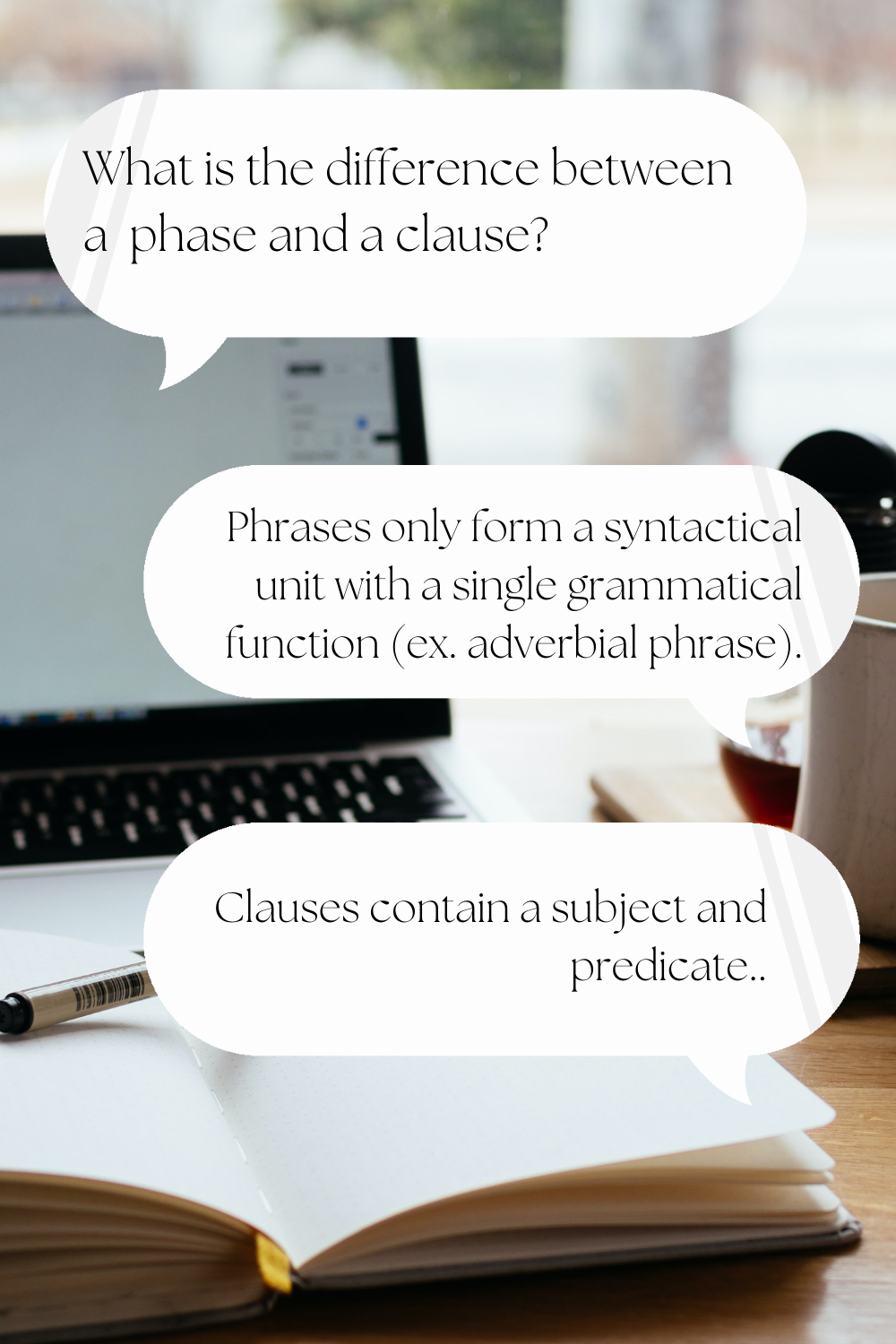

IntroductionIn the last chapter of the Style Series: Grammar 101 post, we learned all about the 7 basic sentence patterns. These form the core of every sentence. Without them, you cannot have a complete, grammatical sentence, or an independent clause. But you may have noticed that your nouns, verbs, and predicates are more complex. Each part of the independent clause can be expanded, or added onto, to create complexity and interest. This is where phrases and clauses, and subordination and coordination come into play. The difference between a clause and a phraseWhen you look up "clause" and "phrase" in the dictionary, their definitions sound similar. Both are a group of words, but phrases only form a syntactical unit with a single grammatical function (ex. adverbial phrase), and clauses contain a subject and predicate. For example, let’s look at the following sentence: When I walked up to the counter, the barista scanned me from head to toe. The independent clause is the barista scanned me (noun + transitive verb + direct object). But as you can see, I naturally made a complex sentence with two add-ons: When I walked up to the counter, the barista scanned me from head to toe. The first part of the sentence is a clause because it has a subject (I) and a predicate (walked up to the counter). It can easily become a complete sentence by removing the introductory when. The final part of the sentence is a phrase because it has no verb but still forms a grammatical structure, an adverbial. What is CoordinationCoordination occurs when you expand your sentence by linking like grammatical structures with punctuation and/or conjunctions. There are three types of conjunctions:

Ex. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; however, they were terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. We’ll explore this sentence further as we review the types of coordination. Types of CoordinationThere are two main types of coordination: coordination within a sentence, and coordination between sentences. indirect objects (noun phrases), and compound predicates (verb phrases). Let’s look at the intrasentence coordination in the example from above. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; however, they were terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. There is only one example intrasentence coordination in this sentence. The compound subject Milo and Greg uses the coordinating conjunction and to form a noun phrase. Below is the sentence recast to create a compound predicate: Milo and Greg danced and sang, and they were terrible at both, which made us laugh.

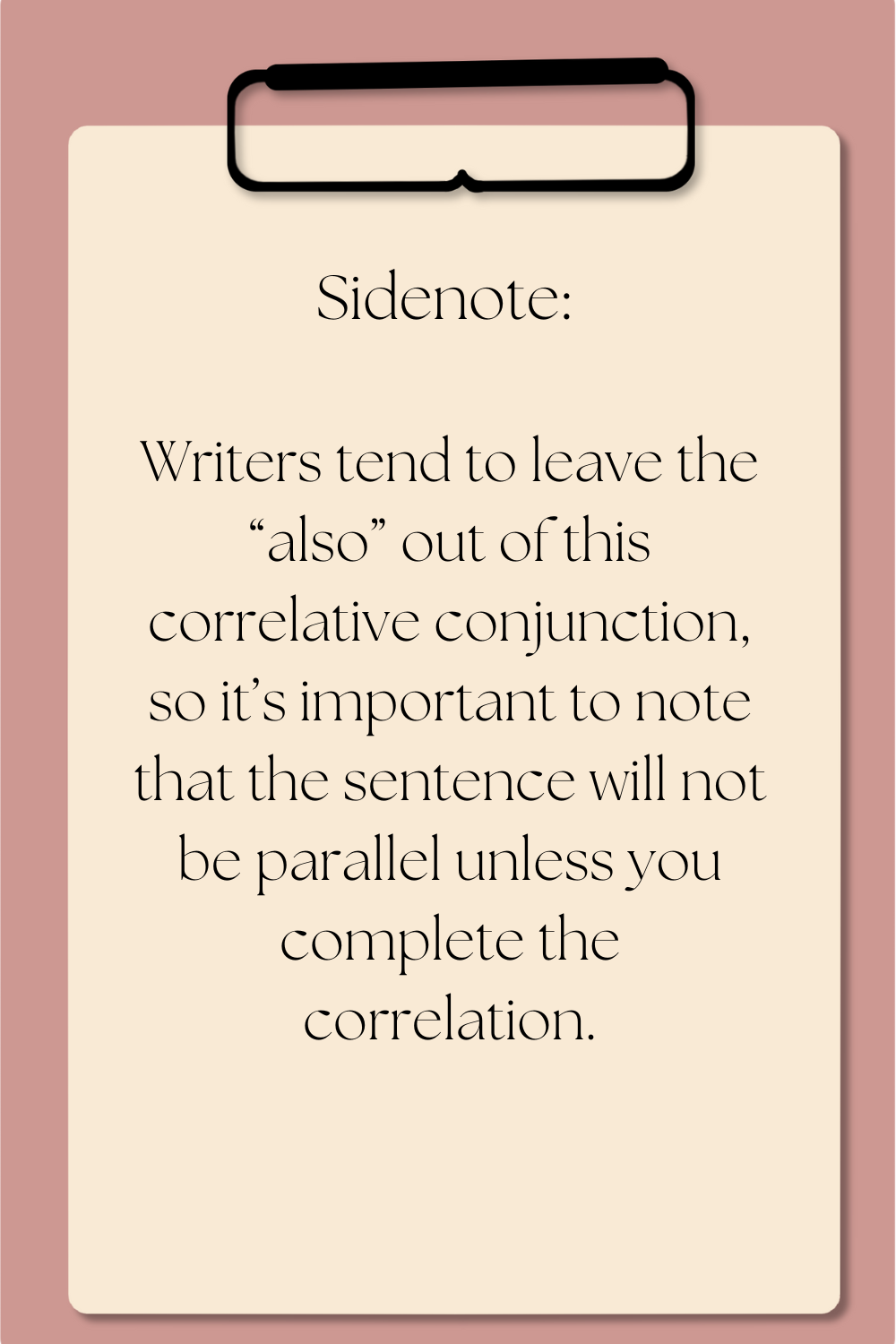

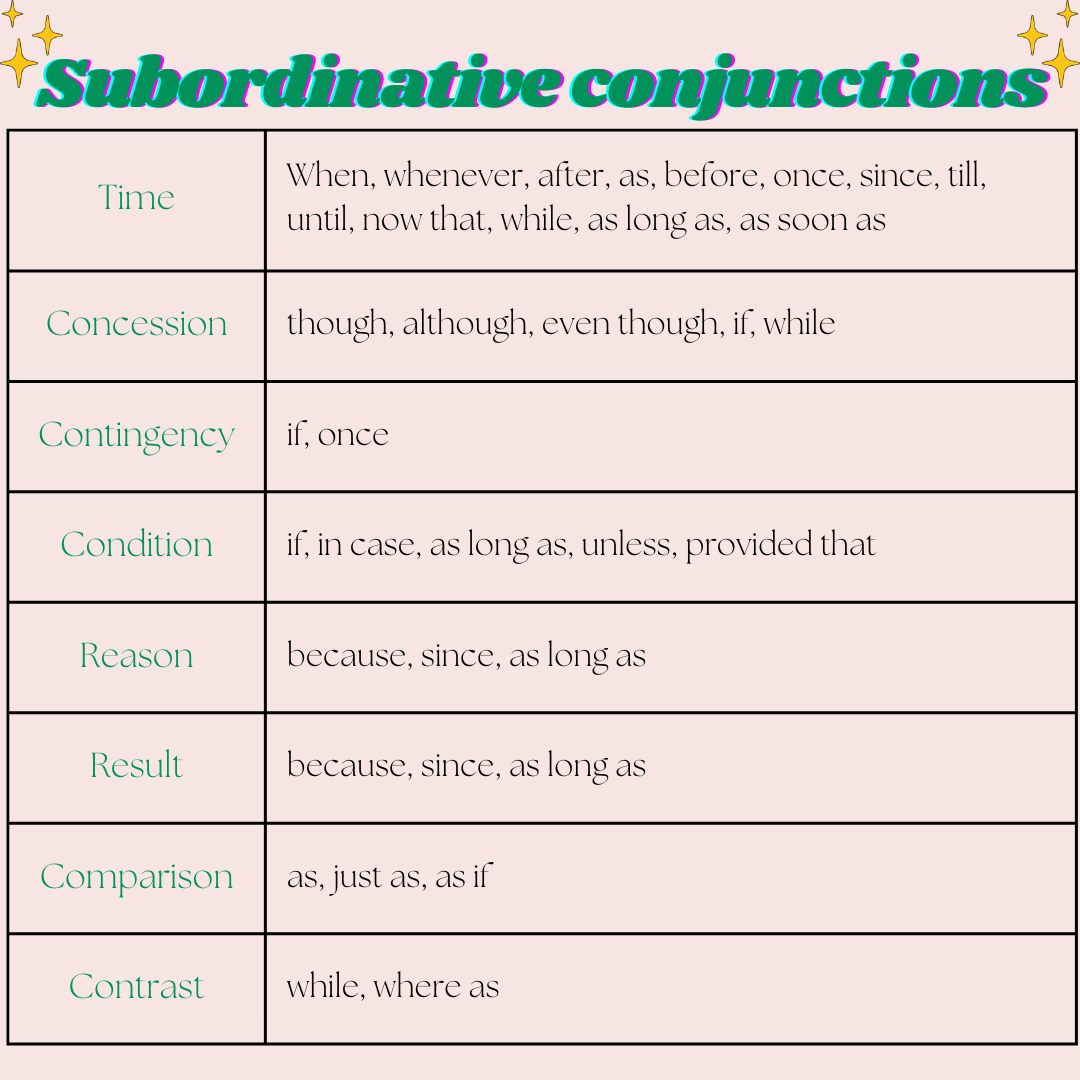

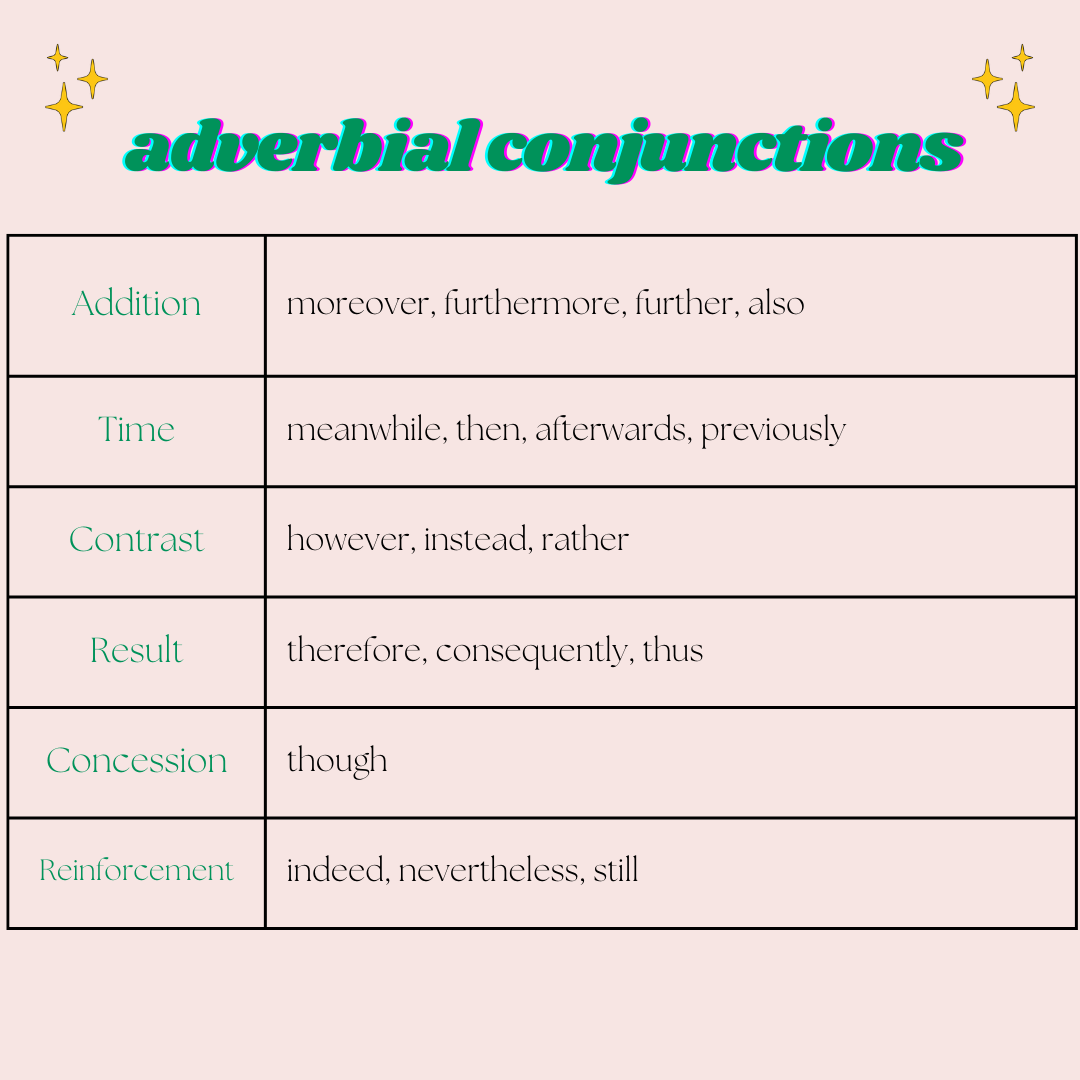

The first type of intersentence coordination uses the correlative conjunction Not only–but also to connect two independent clauses. Notice the Not only clause is an inverted sentence, where the verb comes before the noun, and a different emphasis and rhythm are created. You may have also misidentified this conjunction because but also is split up by they. While not only is always one unit, but also can be together or split up, depending on what you want to emphasize. See how the emphasis changes when new move the also: The second type of intersentence coordination is ; however. However is an adverbial conjunction, and in its current position, it requires a semicolon to prevent a run-on sentence. Like correlative conjunctions, adverbial conjunctions have flexibility. They can move them throughout the sentence to change the emphasis. In most cases, you’ll want to enclose the adverbial conjunction with a pair of commas or a semicolon and a comma. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; they were, however, terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; they were terrible at both, however, and we all had a good laugh. The third type of intersentence coordination is the coordinating conjunction and. (If but wasn’t part of a correlative conjunction, it would be a coordinating conjunction too!) This is probably the simplest form of intersentence coordination, and the one writers, no matter their level of expertise, are most familiar with. Not only did Milo and Greg dance, but they also sang; however, they were terrible at both, and we all had a good laugh. With some exceptions, a comma comes before the coordinating conjunction when it is connecting two complete sentences. Types of SubordinationYou create subordination through dependent (subordinate) clauses. These clauses begin with a subordinating conjunction and include a subject and predicate. There 8 types of subordinating conjunctions:

Types of Subordination There are three types of subordination: adverbial, adjectival, and nominal. But each of these types of subordination has subtypes. Adverbial clauses Like other adverbials, an adverbial clause modifies a verb phrase. They can be tricky to identify because adverbials are movable, so they can appear anywhere in the sentence, depending on what the author wants to emphasize. Therefore, a good clue that you’re working with an adverbial is that you can move it. I used an adverbial introductory clause in my coffeehouse sentence to tell the reader when the barista scanned me: When I walked up to the counter, the barista scanned me from head to toe.

A variation of the adverbial clause is the elliptical clause, in which something is deleted. The elliptical clause is always introduced by either while or when. When you use the elliptical clause, the subject of the main clause is always the understood subject of the adverbial as well. Adjectival clauses Adjectival clauses, also known as relative clauses, are clauses that modify a noun phrase, which includes subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, subject complements, complements, and objects of prepositional phrases. They are introduced by a relative pronoun (that, who, or which) or a relative adverb (where, when, or why). Let’s add an adjectival clause to the barista sentence as an example: When I walked up to the counter, the barista who was steaming milk scanned me from head to toe. There is often more than one barista behind the counter, so by adding the adjectival clause to the sentence, we specify which barista scanned me. We also add a little suspense because of what the barista is doing when they scan me. It hints at their intention (to check me out), and it hints at what may come—some romcom meet-cute shenanigans. Sometimes adjectival clauses that start with which don’t refer to any specific noun, but instead refer to the whole main clause. These are called broad reference clauses. When I walked up to the counter, the barista who was steaming milk scanned me from head to toe, which thrilled me.

In the case of When I walked up to the counter, the barista who was steaming milk scanned me from head to toe, the adjectival clause provides identifying information and therefore no comma is necessary. Nominal clauses Nominal clauses are clauses that fill noun phrase positions. Essentially, if the clause functions as a noun, you have a nominal clause. Two of the most common types of nominal clauses are the nominalizer and the interrogative. A nominalizer is introduced by the relative pronoun that and fills the place of direct objects, subjects, or introduces indirect speech. I suspect that the barista liked what she saw. That the barista over steamed the milk proves she liked what she saw. She said that the barista scanned me from head to toe when I walked up to the counter.

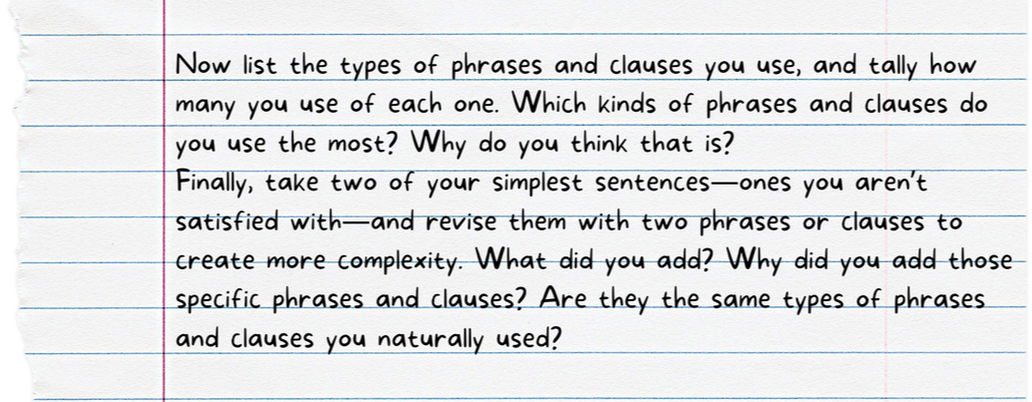

The other type common type of nominal clause is introduced by an interrogative (who, what, when, where, why, which, or how), so I’m going to call it an interrogative nominal clause. I wondered why she was checking me out. Who I was going on a date with was kept secret. I didn’t know anything about how the rules of football work. My main question, why she was checking me out, can only be answered by the barista. While that can often be omitted in a nominalizer, the introductory interrogative word cannot be omitted from the clause. Exercise 3Further ReadingChapter 4, “Coordination and Subordination” in Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects, 6th ed., by Martha Kolln and Lorette Gray

Pages 157–166, 180–185, 201–202, “Coordination and Subordination” in Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects, 6th ed., by Martha Kolln and Lorette Gray “What is a Subordinate Clause,” Grammar Girl blog and podcast Style Series, Grammar 101: The seven basic sentence patterns Style Series: What is a Writing Style |

AuthorSarah Hawkins is a geek for the written word. She's an author and freelance editor who seeks to promote and uplift the authors around her. Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed