What's discussed in this post

Show, don't tell

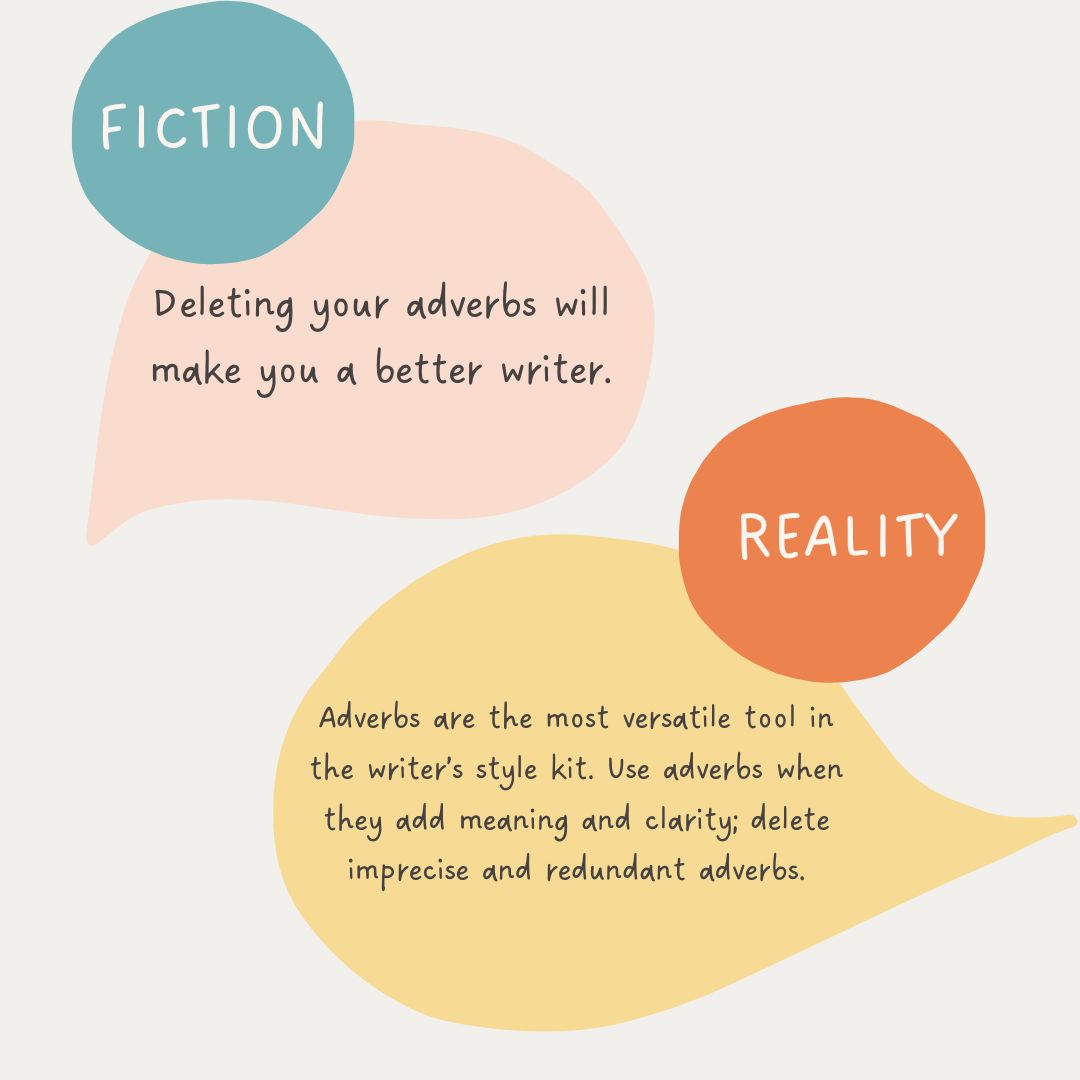

detail in the narrative distance and directing the reader’s focus. Since telling is often framed as bad writing, here are some criteria for using telling effectively: Delete your adverbsacknowledge the type of information they find so troublesome. Adverbs provide information about manner, direction, time, duration, or reason. They are focused on simple-and-flat adverbs of manner, which are often adverbs created from an adjective and the derivational suffix -ly (e.g., softly, happily, quickly). And there is some value in wanting to reduce your use of manner adverbs. If there is a verb that conveys both the action and the manner, the adverb is redundant and should be deleted. If the adverb doesn’t add meaning or clarity to the sentence, it’s imprecise and should be deleted.

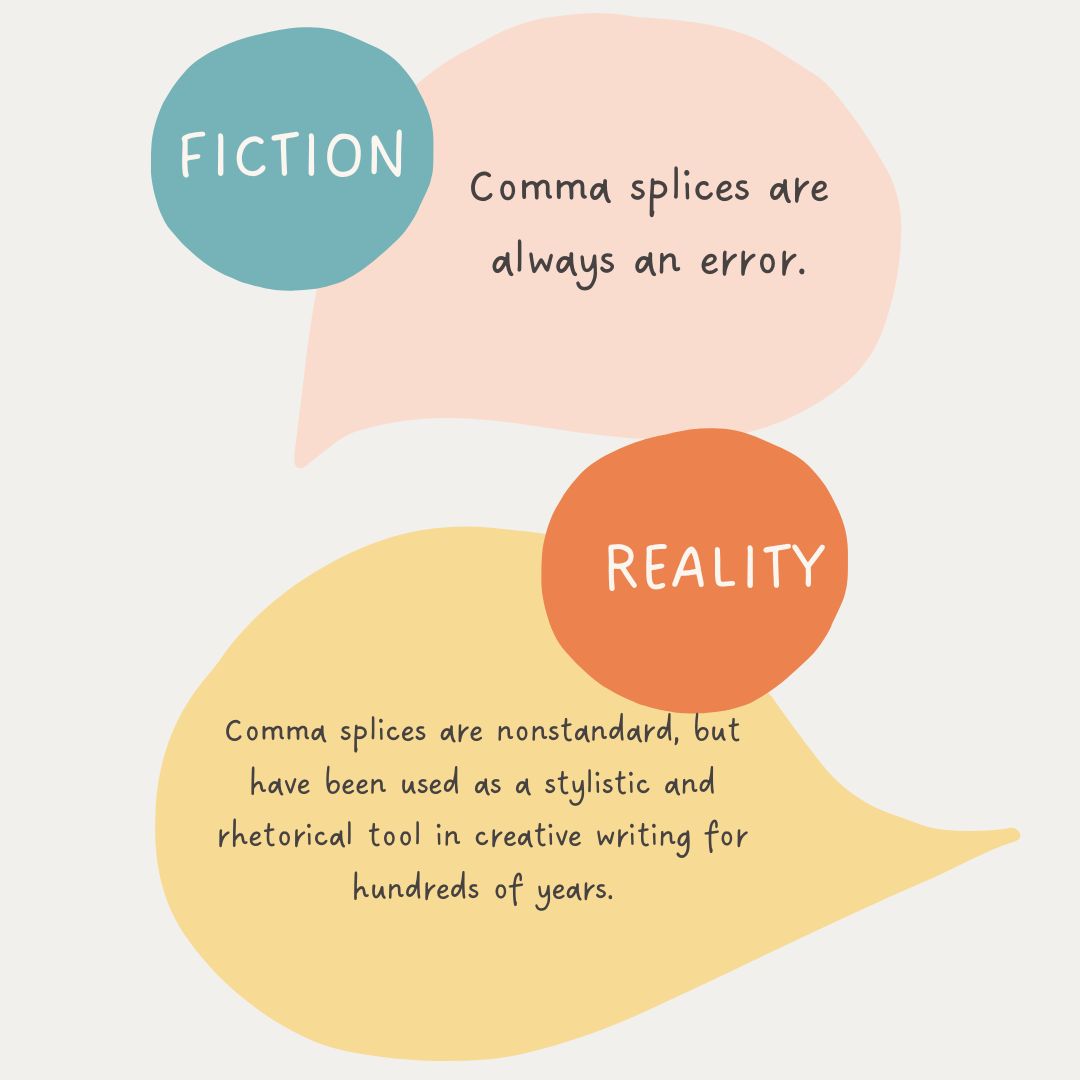

sentence. This is especially true of sentences with intransitive verbs, which take no direct object. If you want to expand I ran, you need to add an adverb or adverbial. So a better way to phrase this advice is: Use adverbs when they add meaning and clarity; delete imprecise and redundant adverbs. Don't use comma splicesI discussed the effective use of the comma splice last fall, but I’ve seen pushback against the use of the commas splice come up again (probably because I’ve advocated for it as a stylistic tool). Yes, the comma splice is nonstandard and most grammar books, therefore, advise against it; but it has been used as a stylistic and rhetorical tool for hundreds of years. Need proof? Dicken’s A Tale of Two Cities opens with a paragraph of comma splices, and my 9th-grade English teacher loved that paragraph so much, she forced us all to memorize it and test us on it.

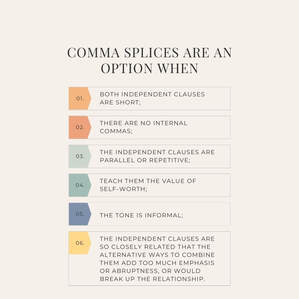

Finally, several reference books I own—including Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace by Joseph M. Williams and Joseph Bizup, Rhetorical Grammar by Martha Kolln and Loretta Gray, Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, The Copyeditor’s Handbook by Amy Einsohn and Marilyn Schwartz—and The Chicago Manual of Style’s “Fiction+” blog acknowledge the comma splice as an option in creative writing. Comma splices are most effective when:

Self-edit tips

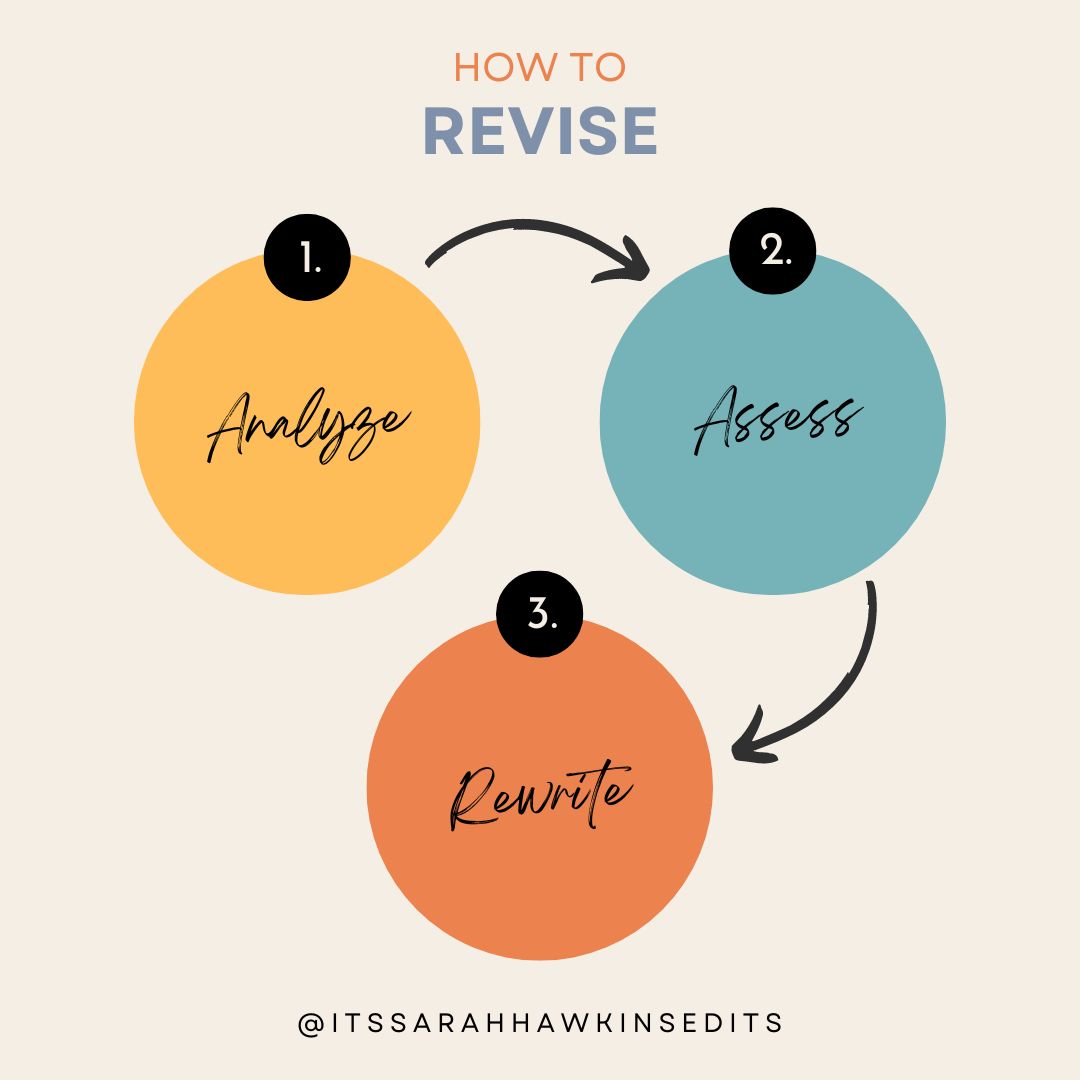

Highlight all the adverbs and verbs in your sentence in two different colors. Analyze: Am I using a lot of the following verbs: linking be, have, make, go, do, get, or take? What kind of adverbs am I using? For comma splices: Many line editors, copyeditors, and proofreaders will automatically correct a comma splice even when it is a part of the author’s style, so the first thing you must do is determine how you use the comma splice, and whether or not you want it as part of your edited style. Ask a trusted reader or your editor to mark comma splices so you can analyze, assess, and revise.

This all helps you learn when you want to stet for style in the future. Stet means “let it stand,” and it’s what authors (and sometimes editors) do when they reject an edit on their manuscript because they think it changes the meaning, rhythm, or tone of a sentence. Make sure you mark anything you stet for style with a comment before you give it or return it to your editor for a final pass. What is a writing myth you've come across on social media? Comment below!Further Study3 ways to use comma splices effectively The Chicago Manual of Style Fiction+ hompage "Comma Splices and Run-on Sentences," The Chicago Manual of Style Fiction+ Using adverbs in fiction – clunk versus clarity “Showing versus telling” in Editing Fiction at Sentence Level by Louise Harnby Oh, the Splices You’ll See!

0 Comments

|

AuthorSarah Hawkins is a geek for the written word. She's an author and freelance editor who seeks to promote and uplift the authors around her. Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed